What Vorarlberg did next

Vorarlberg's new architectural generation has come of age, indeed, is moving into middle age, and some say a new generation is looking over their shoulders. To complement Fourth Door Review 8's Alpine regionalism exploration of Vorarlberg and Graubünden in the themed section, Unstructured 4 looks at Vorarlberg's recent third generation, including Marte.Marte, Cukrowicz.Nachbaur, Nägele and Waibel, and Andrea Sonderegger, and asks whether a fourth generation is co-elescing.

|

|

|

|

| photo by ignacio martinez | photo by bruno klomfar | photo by robert fessler | photo by robert fessler |

But when visiting Vorarlberg - the west Austrian county sitting at the eastern end of Alpine Europe's largest lake, the Bodensee or lake Konstanz - which has developed a continental reputation for its dynamic architectural culture, quite a few presumptions get turned upside down. This small, region, far from metropolitan centres has developed one of the most dynamic continental architectural scenes - over a 1000 new buildings in the last thirty years. Vorarlberg's 360,000 population, after early suspicion, have completely bought into this adapted, variations-on-a-theme Modernist architecture, perhaps because it demonstrates a strong respect, for the regional (and primarily timber) vernacular and tradition. So much so that the community has become a point of pride amongst Vorarlbergian's, in part for maintaining, unusually, its craft, and particularly carpentry traditions, within the county's hi-tech industrial-rural sprawl hybrid.

Vorarlberg is also one of the leading European exemplars of realised eco-thinking, with stringent energy efficient regulations in place, an epicentre of the passivhaus approach, and a building culture where low to zero energy build is the norm. It isn't surprising, then, that the one-time Critical Regionalist tub-thumper, Kenneth Frampton, has been an admiring supporter.

What needs to be added to the county's reputation is staying power. If the first, early sixties, generation - Hans Purin, Rudolf and Siegfried Wäger, Gunther Wratzfeld, Jakob Albrecht, and Leopold Kaufmann amongst others- realised only a handful of buildings, the second, fought long, and, eventually successful battles to establish modern architecture and Vorarlberg's architectural reputation from their radical community, with the social and environmental ethos of the late seventies. The second generation, known today across Europe as the Vorarlberg Baukunstler, architects such as BaumschlagerEberle Dietrich/Untertrifaller and Herman Kaufmann (the big stars of the Vorarlberg architectural community, whose portfolios range from the new Vienna Airport to Beijing, and Shanghai, as well as across various European countries) are today almost the establishment. In the last decade a third generation of architects have pushed their way into the limelight, and the rules have changed again. This third generation include architects Cukrowicz.Nachbaur, Nagele and Waibel, Fink-Thurnher Architekten, Reinhold Drexler, Alexander Fruh, and leading the wave, by common accord, the two brothers, Bernhard and Stefan Marte. If anything defines this generation it has been to find new, and particularly both urban and international, architectural languages that can contrast to the previous waves. Despite these different approaches, there remains a loyalty and commitment to their county. For instance, the two Marte's were actually born in the farm-house, and as the younger, Stefan, remarks, the feeling is almost tangible. "The power we have comes from our roots, … from our home. That's a good feeling. We might do buildings in the city, but we work from here."

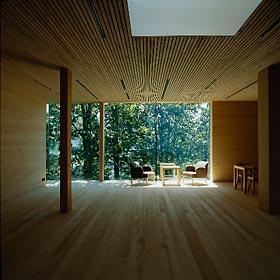

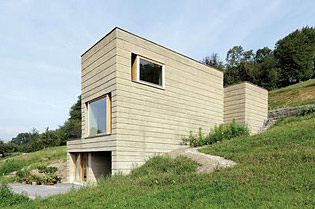

Marte house, Dafins 1999

photo by ignacio martinez

photo by ignacio martinez

Schanerloch bridge,

Dornbirn 2005

photo by marc lins

photo by marc lins

Special School and Dormitary, in Kramsach, Tyrol 2007

photo by bruno klomfar

photo by bruno klomfar

Marte.Marte have become the third generation's leading lights, and their materiality is firmly embedded in the region's attention to detailing. Those who have strayed further from the template have not made so much headway. V.A.I.'s Hämmerle: "Figures like Hugo Dworzak, who are more expressive, they've really got problems in breaking through, as they are a little bit exotic because they don't follow the mainstream."

|

|

| CukrowiczNachbaur's Hittisau Cultural Centre (with village fire station on lower floor... and out of sight) |

Hittisau Cultural Centre photos by hans peter schiess |

Others of this nineties generation have emerged producing striking, if not so iconoclastic, work. Alexander Fruh, Reinhard Drexel and the partnership of Andreas Cukrowicz and Anton Nachbaur. The latter has recently completed Dornbirn's new swimming pool - mysteriously luminous the evening I visited - and an odd amalgam of fire-station and cultural centre in Hittisau village, up in the Bregenzerwald hills. Along with a fair number of residential homes, and a small, beautifully realized chapel, all these projects use local sourced wood for both cladding and structural purposes. Unsurprisingly, Nachbaur says they love using wood, which feeds the low to zero energy standards of many of their projects.

|

|

|

| Dornbirn swimming pool photos by robert fessler |

For several years now quite a few of these nineties practices are part of Vorarlberg's establishment. Marte-Marte have been promoted internationally by Hämmerle's VAI. Bernhard Marte is on its board, and in 2008 produced an award-winning monograph for Springer, and are now working all over Austria, as well as in neighbouring countries. CukrowiczNachbaur have also graduated to larger projects. The latest is adding a new floor to the Vorarlberg's county museum, one of the buildings immediately adjacent to Zumthor's Kunsthaus, looking out onto the Bodensee, and due for completion in 2012. For some, though, these new third generation projects are old news. The future ought to belong to an even younger architectural generation, such as Hein-Troy, Bernardo Bader, Robert Fabach and the Christoph Kalb-Phillipp Berktold grouping, which also includes Martin Skalet and Susi Bertsch.

Christoph Kalb's Wolfurt Fruhlingstrasse housing

photos by Bruno Klomfar

photos by Bruno Klomfar

The core reason, according to Matthias Hein of Bregenz' practice Hein-Troy, is that unless you can demonstrate the necessary track record, young architects can't get their foot on the ladder of the architectural competition system through which many of the Vorarlberg projects originate. "It's been becoming more and more difficult to get up off your feet. For instance, younger architects aren't able to take part in any of the larger competitions. You have to show projects you've done, and if you don't have any references you can't take part. You need to be able show three projects all worth more than three million Euros to be able to participate." Hein, whom

Christoph Kalb's Wolfurt Fruhlingstrasse housing

I'm talking with over the phone, continues by saying there's been a deadline earlier in the day for a kindergarten. "There were eighty applications, from which fifteen will be taken." Hein does, however, believe the situation is improving. "It's slowly getting better. At first it wasn't that obvious what was going on; only a few people were asking, 'Where are the young architects'? And then all of a sudden people noticed the situation, and it has been improving slowly." On a positive note, Hein points out how elders from the Vorarlberg architect community do seem to try and help. Sitting on the juries of some of these competitions some of the older established architects such as Hermann Kaufmann and Much Untertrifaller, have steered the award clients towards some of the younger practices."

|

|

|

| Hein-Troy's Lauterach school All photos by Robert Fessler |

Lauterach school interior |

Lauterach school interior |

Hein himself is skeptical of the line that there is a new architectural generation. "It's really difficult to talk about a fourth generation. If you think of Andreas (Cukrowicz from CukrowiczNachbaur) he's only two years older than myself." As it is

Uebersaxon community centre by night

Robert Fessler

Robert Fessler

Among the other architects, Fabach - who works with his partner, Heike Schlauch, under the practice name Buro Raumhochrosen - have completed a child play area within Daniel Libeskind's massive Bern Westside mall development and another in Dornbirn. Fabach , who also writes extensively on Vorarlberg

Buro Raumhochrosen children's area within the

Westside shopping mall in Berne, Switzerland

photo by Buro Raumhochrosen

Westside shopping mall in Berne, Switzerland

photo by Buro Raumhochrosen

Fink-Thurnher's Community centre and Kindergarten in

Langenegg.

photo by robert fessler

Langenegg.

photo by robert fessler

robert fessler

She points to an industrial estate near to Marte.Marte's Weiler village base, where three recent builds, covering a spectrum of industrial architecture, form the core of a new industrial estate. This includes a showroom for a PR agency by Johannes Kaufmann; a 'very tough, supercool' aluminum box, and what she describes as an interesting modular and sustainable, 'feminine' inflected design for Omicron, an electronics company. In a two-stage design, by NägeleWaibel, the second stage of this three-storey office features a roof-garden, reflecting into the interior atrium of the building. Waibel, over the phone, is more cautious about the feminine inflection. Instead he describes how, given the challenge by Omicron to make a building where working was 'fun', this large open-air atrium is used for volley-ball and other games, while the work-areas for each of the 130 cell-like offices open into customized relaxation areas along the exterior balconies of the three floors. 'The restaurant and rest areas are large', says Waibel, adding that the building has won awards around Europe, but no, 'they don't serve alcohol.' Fun, but not too much fun, evidently.

NageleWeibel's Omnicron Office

photo by NageleWaibel

photo by NageleWaibel

Of the 150 practices currently in Vorarlberg there are very few women practices. Andrea Sonderegger, who divides her time at the Energie Institut ain Dornbirn with architectural work, is one of these. It's evident however, that women run architectural practices are pretty much entirely absent in Vorarlberg. Sonderegger says there may be a few woman architects in the larger practices, but the shots are essentially being called by the men. Women architects might be able to draw in some changes in the detailing, or indulge in some greater application of colour, but in a community which defines itself by the work ethic, the sense that change in this quarter seemed distant and the lack of it a reminder of its cultural conservatism. When I met Sonderegger she remarked on how she loves Frank Gehry and organic architecture, but that getting such designs past clients was next to impossible. "We can suggest things, but we can't manipulate: she states. A recent residential build finished in 2007 exemplifies the work she and her female colleagues are primarily involved in. The home Sonderegger showed me is a passivhaus, for a

Andrea Sonderegger's passive rammed earth house, from

outside and interior details. Andrea Sonderegger

outside and interior details. Andrea Sonderegger

homeopathic doctor, its interior beautifully decked out in a New Age minimalist hybrid. It was another rammed earth building - so it could "disappear back into the ground" according to the doctor, - and the interior walls were again finished by Martin Rauch. Trained as a ceramicist, Rauch's finishes can give the sense of an alchemist at work, transforming humble soil into something remarkable, a fact underlined by presence in Basel the week I saw Sonderegger's house, He was finishing Jacques Herzog's (of Herzog & De Mauron) wine cellar walls. Rauch's walls, complemented by another craft technique, the luminous colours of the felz matting on various of the cupboard doors, were also reminders of how crafts' broader terms of reference, alongside the ever-present carpentry and wood buildings, has been maintained in Vorarlberg. Sonderegger was pleased with both the building and with Rauch's finish, but her work, and others like her, will go largely unnoticed among the male dominated offices of the principal practices. While a Zaha Hadid might never have been likely to emerge from the region, there also isn't a major female figure on a par with, for instance, the French architect, Francoise Jourda.

Haus Rauch - exterior. Beat Buhler

For his part, Rauch's own name-recognition continues to increase, not least because of the completion of his own home, which is a showcase of sorts for his rammed earth techniques, and triggered a round of articles in many European architecture magazines. This latest flurry of articles was connected to Rauch's choice of a non-Vorarlberger and contemporary of the third generation Swiss architect Roger Boltshauser, to design Haus Rauch in Schlins, for some a telling choice. Boltshauser, from Zurich, has built a reputation as one of the new Swiss generation of modernists, absorbed in the complexities of primal modernist forms. Interestingly, for both a region and a rammed earth specialist, so strongly identified with sustainability, Haus Rauch, reaches for a steel rather than timber structural frame.

Haus Rauch - interior. Beat Buhler

Haus Rauch's rammed earth walls, reflect the continuing emphasis on craft remains at the heart of Vorarlberg's architectural culture, and Vorarlberg's carpentry organization, Werkraum have conscripted none other than Peter Zumthor to design a visitor and sales centre for the furniture makers, carpenters and felt makers who comprise the majority of the province's craft community. The building, which at present, looks as if it'll be completed by the time of Werkraum's next bi-annual show in 2011, is to be in the Bregenzerwald village of Andelsbuchs. This is home to one of the most active craft families, brothers Johannes and Anton Mohr, who work as upholsterer and cabinet-maker respectively.

Back in Bregenz, Hein talks of the most exciting current project: the master planning for the SeeStadt, a significantly sized piece of land between the lake and the town, which has been on people's minds in recent months. Five offices have reached the final round in the competition, including BaumschlagerEberle teaming up with the current British darling of the continental Modernism scene, David Chipperfield, and CukrowiczNachbaur with the somewhat less exotic Riegler-Riewe Arkitekten from Graz. Hermann Kaufmann and DietrichUntrifaller head up two of the three remaining entries, adding to the impression of the established big names as the ones consistently getting through to final rounds of competitions. The winning team is to be announced in April.

|

|

| Computer renderings

of CukrowiczNachbaur's Bregenz museum project. CukrowiczNachbaur. images cukrowicznachbaur |

All the older large practices are trying to expand their operations across Europe and wider afield, emulating BaumschlagerEberle, the big elder brother success story, who have been working internationally for some time. These attempts are happening with varying degrees of success. And for all their claims to difference, this is also the brother's Marte's desire, a wish to escape to more challenging, and what they perceive as more extreme projects in the wider European world. At present these projects seem to come down primarily to other parts of Austria, including a museum project in Fresach, Southern Austria. As already mentioned Cukrowicz Nachbaur are also working on their largest cultural project to date, extending skywards the county museum in Vorarlberg, but there are not that many projects for any age-range of architect to get their teeth into. If there is evident frustration among both of the third and the slightly younger,

CukrowiczNachbaur's Bregenz museum project.

This is an updated version of an unpublished piece originally written in 2007. It's intended to complement the Generation Graubünden piece, which looks at the new young architectural generation in Vorarlberg's neighbouring Swiss canton, Graubünden. There are further articles about Vorarlberg on Fourth Door's timberbuild site, Annular.