WALTER BAILEY: Natural forms, Human endeavour

Walter Bailey's sculptures are another layer in Sussex's arts, architecture and crafts ether. Their intricate lattice patterning are a signature Bailey leit motif, another whorl in the whole wood-weaving terrain. On the eve of the opening of a major series of works within an up-market London development, Kay Syrad talks with Bailey about how recent years have seen the appearance of new turnings on his sculptural path.

The barn is divided into open and closed sections, the open part being the old byre. Metal trunks and shelves hold Bailey’s extensive collection of tools (wood planes, pliers, wire brushes), and chainsaws and saw blades (mainly18” and 20”), kept under a heavy cloth. There are boots, guards, ear-and-eye-defenders and helmets, evidence of the heavy, dangerous work that may seem incongruous with the often delicate, light-filtering, rhythmical forms that Bailey produces.

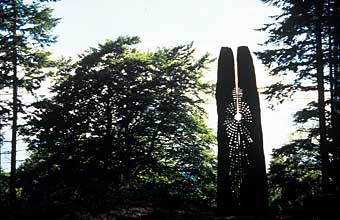

This is not the first time Bailey has experimented with realising the Platonic solids.(1) Indeed, he would argue that no sculptor can ignore them, that they are the basis of form, and in fact Neolithic carved stone sets of the Platonic solids have recently been found in Aberdeenshire, dated c. 4000 BCE (now in the British Museum). In the 1980s, Bailey worked as an assistant to David Nash in Blaenau Ffestiniog in North Wales. Nash is renowned for his Platonic solids, and Bailey worked with Nash on several series of Solids at that time. However, the dodecahedron was the one he had never tackled, the Solid that is symbolic of ether. Finally, in his 50th year, Bailey became intrigued by its being central to the Greeks’ mystery tradition: it was the hidden form in Platonic times, and has more recently been thought to represent the cosmos. Early on, when Bailey was making sculpture for Nash, he said to Bailey, ‘Ah, you’ve got a Celtic spirit...you’re unable to carve a straight line’ – and the work is Celtic in the way that nature is always woven through it. Bailey says he can carve a straight line now (see the dodecahedron) but most of his works are indeed made up of curves. Bailey describes a sense of nature or human energy coming through, in and out of the lattices, as in the calligraphy of the Lindisfarne Gospels, for example, where geometric patterns, plants, animals and birds are entwined in the letters, representing ‘oneness’, a unifying force. Through Bailey’s latticed works you can see the landscape, as if the figures are, as he says ‘wearing the landscape’ or ‘existing as a fruiting body of the landscape’ - not at all separate, but seamlessly belonging to, the landscape. This view is similar to that of the artist Chris Drury, in which the division between nature and culture, nature and human, is seen as an illusion.

Bailey’s first lattice works – ‘the beginning of what I would say was my true voice’ - were a series of harvest figures and ‘ancestors’ exhibited at Lewes Castle in 1994 along with a work by Drury

It strikes me that whilst an increasing number of environmental artists are engaging with science, the division between art and science seems strangely irrelevant when considering Bailey’s sculptures – not because he isn’t concerned with science but because he is – in the sense of being, like Darwin himself, a close, fascinated and respectful observer of nature. But he doesn’t just ‘see’ nature – he apprehends it with all his senses, his entire body reckoning, in every new work, with the age, grain, texture, malleability, strength, weight, scale and colour of the wood he is using; and also with his own cognitive capacity, muscular strength and skills, the kinetic intelligence contained in the very subtle judgements of the body in carving such delicate, latticed patterns with the chainsaw.

Whilst these physical imperatives are significant, Bailey’s belief in the unity of all things is also based on an extensive knowledge of universal patterns – he shows me Chladni’s 1920s images of sand on metal plates forming into patterns in response to vibration – whenever a note is played at 2150 hertz, for example, an identical pattern forms. For Bailey, this amorphic energy is not something simply to be observed outside ourselves, but works in the same way within us: we move into different forms; our self-organisation changes, in response to even the most subtle vibrations.

At the local museum they had an early dug-out canoe next to a massive piece of rope that shipbuilders had made in the 19th century that made this hotch-potch of historical connections, which I loved and which I mourn the loss of after the clarity that came into curating museums [...] I love the idea of this jumble, of ‘throw everything in’. I guess art is a bit like that, how you collect the vision in some way. You do throw in lots of things [...] and you produce these associations.

Bailey’s family had few books so he went to libraries, collected old encyclopaedias, copies of National Geographic and Sunday supplements from skips. Now books line the walls of his cottage, playing a key part in the way he develops his ideas for each work. Bailey has owned Frazer’s The Golden Bough ‘all his life’ – first discovered in a small library in Seaburn, Sunderland. He has long had a fascination with mythology, anthropology and fairy tales, with our links to the past through oral traditions. His intuitive understanding of the ancient knowledge contained in symbolism, and the psychological insights that can be found in alchemy inform Bailey’s thinking about our relationship with the elemental; about the transformation of matter and spirit. His world view is encapsulated in the Hermetic maxim ‘As above, so below’ - macro-cosmos and micro-cosmos as reflections of each other. And broadly sympathetic to Steiner and anthroposophy, Bailey’s work is founded on the idea of everything being connected, not in a religious sense, but rather in the sense of a living universe, or in one of his favourite science fiction writers, Philip K. Dick’s conceptualisation: VALIS - a Vast Active Living Intelligent System. Anthroposophy would argue that DNA is a structure that has life breathed into it – a receptor rather than the thing itself.

One of the remarkable features of Bailey’s work is its ability to hold or contain transformatory human experience. A number of works are concerned with journeying over different stages in one’s life, from trauma towards healing. Back in 1994, for example, he made Warrior, a latticed work made from yew. At that time he was reading Healing into Life and Death by Stephen Levine, a series of interviews with AIDS victims who spoke of finding their ‘heart-centre’ through illness and beginning for the first time to feel really alive.In 1995 he was invited to work at Grizedale, after his son, then aged seven, had been temporarily paralysed and critically ill with Guillain Barré syndrome. The first of three Grizedale pieces was the iconic Cloak of Seasons, carved so that light penetrates the darkness of the oak.

Bailey has long been interested in human pre-history and early artworks because of the more direct relationship early peoples had with the energies and forces of the earth. A work that embodies this interest is his Oak Stones (2005) made for Leith Hill, Surrey, run by the National Trust and facing the view from the North Downs to the South Downs near Leith Hill Tower (an area associated with the composer Vaughan Williams). The National Trust commission came about because these views across the Weald had been opened up by the clearance of trees to restore historical views (100 years before). Bailey’s three pieces resonate with ancient stones (dolmen) and there has been enormous interest in the work, with many people photographing it, some using time lapse to film streams of light pouring through.

A theme Bailey has used from the beginning of his artistic life is indeed origins. Also in 2005, on a three-month residency at Kew Gardens, he made a number of works for a commissioned exhibition using storm-damaged trees. During this time he lived on site in a caravan, setting up an outdoor studio under a canopy of trees, making sculptures that continued to explore his fascination with seed heads. Prior to that, at Wakehurst Place, which houses the Millenium Seed Bank, he made Dream Body (2003), from a ten foot oak. This piece was inspired by a story from the Jaine monks: the frame holds the outline of a figure and on the base plate are imprints of two feet, symbolising the moment the Buddha moved away from material form, the energy space still resonating with his earlier presence.

Bailey always uses oak for such intricate work, in which there is a fine line between the risk of breaking the wood and getting the degree of delicacy required. This is the most exciting moment in the making, in the whole journey from choosing the tree to completing the pattern. He is using what he calls a very crude tool to express very delicate and intangible energies.

In 2005 Hamilton Associates Architects (subsequently Robin Partington Architects) commissioned Bailey to create sculpture for Park House in Oxford Street, London, taking a new approach to commissioned art by incorporating it within the fabric of the building itself. It is the biggest building project on Oxford Street for over 50 years and covers an entire City block. Working with a dynamic and forward thinking group of architects who had previously worked with Norman Foster (on the Sage, Gateshead) and Rafael Vinoly (on the Curve, Leicester) Bailey was invited to explore possibilities for public art throughout the building. The commission has been seven years in the

Bailey created the Park House designs using controlled gestures with ink and a squirrel-hair brush, all the time looking for a common language throughout the building. Each of the glass or wood panels are split in half, a pattern resonating across the split, representing what Bailey describes as ‘the clamouring orchestra of history and information inside, looking for some sort of synergy; looking for essences – in a simple form that could hold a net of meaning’. It is another attempt to make the invisible visible, in particular what he calls the energetic quality of the divided thing. He is exploring the language of a gut feeling, the space where the forces come in from somewhere else – a connection between earth and heaven, the cosmos and the sun. So much of Bailey’s work is divined from botanical processes, which are themselves ‘very much about sun forces and their harvesting.’

At Park House, Bailey worked for the first time with glass (in fact, white frit, which is ceramic baked on to glass), working with glass experts to create the 76 ft long pieces. In the design process he’d had to make a false floor and false ceiling in his studio, and using rolls of 2m wide paper, formed a scroll to accommodate the length and rhythm of his brush and ink drawing. It was then sent off to be digitised and a screen print made of the drawing, with brush strokes still apparent, showing the relationship between his hand and the finished piece. Bailey wanted the frit on the outside of the panels, facing on to the street. First of all the architects said ‘no’, that because of the environment the frit would get too dirty - but it was precisely the interaction between the glass and the environment that was, for Bailey, exciting – as he puts it, ‘a riff on things we can’t control’. I recently saw Bailey’s panels from the top deck of a London bus: the pattern on the glass looks as if it is falling down to earth, coming towards you and yet slipping away from you at the same time.

Alexandra Children's Hospital, Brighton

If trauma plays out physiologically, as shapes or patterns of embodiment, it is suggested here that sculpture, understood after Rosalind Krauss as occupying an expanded field of bodily relationality, functions as something like a stage on which healing transformations can be imaginatively performed [...] in the face of a threatening world.(2)

This makes sense to me in relation to the repeated patterns in Bailey’s work, its insistence on bringing light through the dark, and also to how he draws our attention to the way natural forms occupy, even determine, human endeavour. The sense of trauma Wood talks of isn’t only personal, of course, but can be applied to the impact of both the destruction of the environment and the compromising of our human relationship with the earth. Wood goes on to say that ‘The experience of the sublime reanimates the tension between our power and our fragility’(3) and this, too, speaks to Bailey’s mastery in using the aggressive power of the chainsaw to create that which is tender; setting wood on fire, but always catching the wood before it is destroyed. This symbolises the necessity of, the inevitability of, seeking the dark - feelings of chaos and potential destruction push you forwards - but you also need ways to heal that shadow side. For Bailey, the resonant words in that process, the ones that make sense to him, are reverence, gratitude, the miraculous.