North of the World – Sami Rintala

The continent crossing Finnish architect, who's helped Trondheim's Live Studio's and TYIN Tegnestue, get underway, and, with his Rintala-Egertsson studio, designed a plethora of small one-off projects and workshops in Norway and around the world, is changing tack. Rintala is going local, with a new focus on his adopted home, the northern town of Bodø, and the Norwegian High North.

Sami Rintala, the Finnish architect, may live in Bodø – the other side of the Svartisen glacier mountain borderline which separates the long Atlantic coast-line with the beginnings of Northern Norway proper - but his influence on Trondheim and its youthful architectural scene has been critical; both kick-starting and transforming its prolific live building culture into a scene with genuine momentum. Rintala's influence has, however, has also been considerably broader and deeper.

“There are two sources to this live building culture in Trondheim,” says Hans Skotte, the architecture school’s wise-elder of a professor. “First, all the students are thrown into doing a live building project during their first term. The other is principally the influence of Sami Rintala, who introduced the workshops he’d already been doing, to Trondheim. There’d been workshops before but they were erratic, and more abstract fashion. Sami made them socially focused and more meaningful. He’s extremely inspiring.”

By the time Rintala began at NTNU in 2005, he was already establishing a reputation as a peripatetic workshop leader in architecture schools and out of the way places across the planet. Underlining this, were a half dozen years of art-architecture installation projects across an equally expansive canvas closer to the globe’s more Northern latitudes. These three foci, Norwegian and other teaching projects, international workshops, and working as co-founder and most visible partner of the quasi-nomadic Rintala-Eggertsson studio, are at the heart of Rintala’s working life.

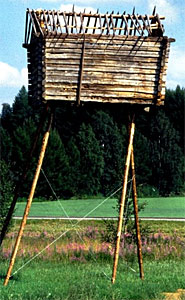

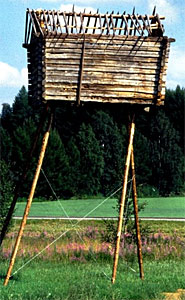

Heggmoen Campsite, one of Rintala's recent workshops out in Northern

Norway's back country – Photo Pasi Aalto

Hut to Hut prototyoe project near Kumta

in Karnataka, India – student project 2012 –

Photo Pasi Aalto

Far end of Bodø marina on a midsummer's day –

Photo Oliver Lowenstein

The studio started small and has stayed that way. Founded in 2007 with Icelandic architect Dagur Eggertsson, and joined in 2009 by Vibeka Jenssen and more recently by Thea Dahl Orderud, Rintala-Eggertsson’s focus has been on the kind of small scale art-architectural inflected work which has proliferated as a typology and practice all of its own over the earliest years of the new century. One reminder that the studio is Nordic rather than Norwegian, is the stripped down Nordic Functionalist aesthetic that the work is characterised by, pre-dominantly in wood, with a clean, straight lined simplicity to the forms that at times feel out of kilter with some recent Norwegian architecture – Helen & Hard and Jensen & Skodvin come to mind. This makes sense in a post-internet age however, when both founders are from outside Norway, their offices shared between Oslo and Bodø and a significant proportion of other of their projects from across the world. It has meant that air travel is now a major part of Rintala’s life, something he seems to have embraced tirelessly; using the studio’s public media face to both promote projects into the media’s path, and to network through the talks, architectural events and workshops in different parts of the world that he participates in. Sociable and friendly, his workshops have become very popular, not least at NTNU, where, according to Skotte, he is the architecture school’s most popular workshop tutor.

Currently, in a mind-shift which has been underway for the last few years, Rintala is devoting more of his energies focusing on work across his immediate terrain – the southern edge of Northern Norway and adopted Norwegian home, Bodø.

Walking barns – the 1996 Land(e)Escape project with Marco Casagrande

Photos Rintala/Casagranda

Rintala had recently moved to the gateway town at the southern edge of Northern Norway proper, when I was first told about him in 2007, by

Pekka Heikkinen, who runs the

Wood Program - at their shared undergraduate architecture school, Helsinki’s University of Technology’s (HUT) these days rebranded as Aalto University. “He’s a bit different” Heikkinen said, before speaking about the individual path his Finnish peer and colleague had pursued, and which I discovered for myself when I visited him in Bodø, the following summer. Talking to me about his early years then, Rintala described how he’d driven across Siberia and post collapse Soviet Union to the Pacific in a week, taking photographs all the way; how a fair proportion of his earlier years had included working on private houses and art projects in far flung parts of the world, from the Arctic to Korea, China and Japan, but was now setting up a practice in Oslo. Later I learned how he’d moved to Norway: Rintala meeting his future wife, Heidi Ramsvik, and then moving together to the Norway’s High North, back to her hometown.

Along the way a series of art installation pieces emerged, and his description of those first years summon up images of a young man’s story: the great adventure, adrenalin and excitement, the ‘Go East’ energy. After leaving HUT in 1999, his first early partnership was with Fellow Finn, Marco Casagrande, which lasted through to 2003. But it was his father who ran a construction company in Espoo where he was born - who gave him his early building experience he says, “learning how to use tools.” Then the first years in school spurred his early architectural steps, drawing together culture, photography, and from 1993 onwards, modernist form, before taking courses with Finland’s pre-eminent architectural theorist and phenomenologist,

Juhani Pallasmaa. It turned out to be completely formative. He began to investigate art more deeply, and acknowledges Pallasmaa’s influence on his architectural thinking by the time he graduated.

Torch slaughter – Photo Rintala/Casagrande

Photo – Rintala/Casagrande

Pallasmaa’s influence also helped spur the experimental and explicitly environmental land-based work of Casagrande and Rintala, and brought them closer attention. But for Rintala, in those early years, there is much taken from phenomenology’s book - lived experience and learning in the physical world, not least in the workshops - which would gradually begin to crowd his working life. However, when they went their separate ways with

Casagrande gravitating towards a more organic architectural language, rooted in the continuing hold of his Far Eastern experience and philosophies; Rintala never forewent the functionalist simplicity he first encountered at HUT.

Possibly their most poetic project of the period was Maaltapako, or Land(e)scape from 1999, a series of remnant barns, raised on timber stilts or legs high above a Finnish field near Savonlinna; three small log buildings, which had fallen by the wayside with the coming of Industrial farming, their function of protecting animals and storing hay, no longer needed. The installation celebrated the old ways of Finnish farming, while also protesting the extending intrusions of the city and its suburbs into the countryside. During the long winter, when farm animals would have been slaughtered for food, Casagrande & Rintala brought the story full circle, torching the barns, by laying tinder beneath their raised bodies, while Finnish dancer Reijo Kela performed a traditional slaughter carnival celebration, and all three structures burning to the ground in this ritual fire ending.

Blood red rum in Anchorage, Alaska

Photo’s Rintala/Casagrande

Atmosphere, ritual and the elements of nature have continued to play a significant role in Rintala’s work, part of a clear environmental overlay; suggesting to some that this early work was as much land art as it was sculptural architectural installation. For his part in a recent email, Rintala acknowledges the influence and importance of 1970’s land art to him, and also Eggertsson. Interwoven and surfacing early if intermittently, is a political undercurrent pulsing through Rintala and his work, in one project or another. A further collaboration commission with Casagrande in the midst of Bush the younger’s 2003 Iraq invasion, took the two to Anchorage, Alaska, where they worked on

Redrum. Composed of discarded giant rust-embossed oil drums, with blood red painted interiors, above a floor of oyster shells - the source of Alaska’s oil, the installation was, according to Casagrande’s site, a comment on the interconnectedness of oil, war and environment. The Canadian

Globe and Mail wrote that it was “a slap in the face to Alaskans.” Redrum, in case you missed it, reads ‘murder’ written backwards.

Years later, Rintala’s collaboration with Skotte, and their students, Andreas Gjertsen and Yashar Harsted - soon to set up as TYIN Tegnestue – emphasised again the political undercurrent of some workshops. Underlining – albeit physically, rather than in words, Skotte’s oft made contention that architecture is a social act. Separately, Rintala states a conviction that every architect needs to participate in the workshop experience, before describing a cycle of workshops at different scales of complexity intended to develop students further.

Edge Conference, Jyväskylä, August 2009 – Photo, image Aaalto Foundation

Another unrepeated instance of this social dimension, was his 2009 curatorship of the Aalto Foundations tri-annual architecture conference. Titled

Edge: Paracentric Architecture, the conference brought many members of a new generation of world architects together in Aalto’s adopted home city of

Jyväskylä - see an in-depth discussion in the piece in

FDR9, which pivoted between humanitarian and broader Global and South architectural cultures.

Ground Up Architecture Walls & Bridges – The speakers Rintala had brought to

Jyväskylä also hinted at some of his extracurricular interests by drawing in some themes closer to home. These included Saami artist

Geir Tore Holm and, starting the conference off, the Finnish Ecologist,

Yrjö Haila - who sought to frame architecture in a broader ecological context with a talk titled

Embedded in the Biosphere. I had already noticed an interest in the natural sciences, with both

Edmund O Wilson’s Biophilia and

Jared Diamond’s societal

Collapse, sitting on a bookshelf, when I'd first visited him the previous summer.

Jyväskylä,for Rintala, was a chance to push these politically inflected broader brush strokes to many across the Nordic architectural world, for whom the late summer Aalto conferences are a tri-annual fixture.

Santiago, under the volcano

Photo – Open Source

Some time later, during a phone call for another interview, Rintala spoke of returning from Argentina and concluding that he was too Nordic to relax each time he took an evening walk wandering round Santiago; experiencing the hyper extreme wealth/poverty gap between the inhabitants of the favela slums and his super wealthy Chilean hosts - who didn’t appear to give this crushing inequality a second thought. When he recounted this story I was reminded of the Bjork line,

‘I thought I could organise freedom, how Scandinavian of me.’

Rintala is Finnish, not Scandinavian, but with his move to Bodø, these Nordic distinctions muted. His role in the semi-nomadic Rintala-Eggertsson partnership, working from his Bodø home office but constantly in virtual touch with the main Oslo studio, underscored the remade borderlines. This network nature of the practice is multi-layered, and an instance of the paracentric architecture on show in Jyväskylä; far from the traditional architectural centres of influence, yet international in reach. At Edge, the conference was a reminder that those who don’t live in or work out of the Nordic regional centres – the Copenhagen’s, Stockholm’s or Helsinki’s, drive practices into heterodox strategies for framing and projecting their work to the wider world. Rintalas’s Finnish peer, Anssi Lassila, renamed his studio, the Office of Peripheral Architecture or OOPEAA , dry Finnish humour applied to working out of his home-town in mid-Finland, Seinäjoki. For Rintala-Eggertsson however, the multi-layered has long been manifest in shaping their Norwegian base at international level, both in workshops and art-inflected projects.

Floating Sauna - Hardangerfjord, 2002

Photo Rintala-Eggertsson

Rintala and Eggertsson in the rain at their Seljord lake Look Out towers in 2010

Photo Abraham Thomas

Rintala-Eggertsson have become a fixture amidst the international and peripatetic cast who populate this loosened space of art-architectural crossovers these days, regularly shuttling from exhibition installation, to sculptural showcases, to workshops in different parts of the world. Invariably if you try and make contact with him, he is in one remote part of the world or another; even if these remote places could often be a huge megacity like Shanghai, or just an old-fashioned 20th century scale city like Vienna, for instance. In this, Rintala is a significant player in the expanding band of architects who, while working on orthodox projects have made their names in part through their involvement in small, bespoke cultural one-offs. These smaller, more modest anti- or counter-iconic works, are counterpoints which still relate to large-scale iconic projects. They’re commissioned, designed and built with every intention that they'll draw people to them, though are, smaller scale, and generally ‘less in your face’ full-on attention seeking of the starchitect ‘wow’ statements required by world cities. They populate exhibitions and festivals taking on roles in local community events, physical expressions of the steadily increasing role of cultural tourism worldwide. The elder of this still coalescing tribe is Peter Zumthor; although increasingly, the cast is drawn from the post Great Recession wider horizons of China’s Wang Shu, Russia’s Alexander Brodsky or Burkina Faso’s

Francis Kéré, as well as architects from the twentieth century West.

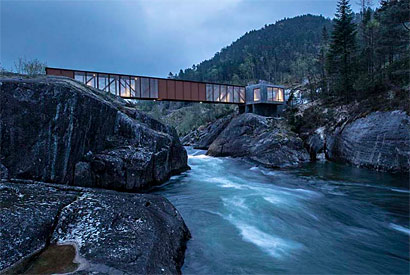

Facing North – the Kirkenes Micro-Hotel – Photo Rintala-Eggertsson

Throughout these years however, there have also been projects both in and relatively close to his Bodø home. For instance, Northern Norway, Finland and Russia’s polar tri-borderland on the Kola peninsular particularly round the largest functioning town Kirkenes. Rintala has had an off-on long-term connection with Kirkenes, and its

Barents Spektakel festival. In 2006 Rintala-Eggertsson began on a design for a

micro hotel – the smallest in the Northern Hemisphere. Situated on the shoreline and functioning as a place to stay, it was in place for several years before again being ritually burnt in the deep winter of 2012. And it would seem that these elemental gestures add another layer, this time temporal rather than spatial, connecting to the pre-industrial, traditional ways of living and working; or at least bringing critical commentary to industrial society’s steady colonising of the past, as well as the rural. For the Nordic world – whether Norway, Finland or Sweden, it is the high North which is the nearest that city southerners can get to their own cultural and geographic other. This spacious wilderness and wildness is symbolised most fully by the Northern world’s own nomadic tribes, the Saami people – whose identity and culture somehow persist alongside encroaching modernity. For

Magnus Jørgensen, in an essay in Oslo 0047’s 2009

Northern Experiments exhibition catalogue, it’s the ‘otherness’ of the periphery, the Saami culture combined with the very distance from the urban post-industrial mainstream, which provides Rintala the freedom to explore an architecture which, among its roles acts as a critique of the discipline’s mainstream orthodoxies. How far one can take, as Jørgenson does, this as an instance of Kenneth Frampton’s ‘Architecture of Resistance’ is a moot point; but it is not irrelevant that this southern Finn has his home near to the Arctic High North.

After the move north to Bodø, Rintala appears to have quickly integrated into the local and regional scene. Alongside building a house for his young family, there has been a bus stop project in the town, together with a role in the

Lofoten Island’s international art festival. Here, a Rintala version of the beautiful stockfish or Fiskhjelle drying racks, was constructed at the harbour’s edge approach to Svolvaer, the archipelago’s principal town. Subsequently, another higher profile abstracted Fiskhjelle became part of

SALT in 2015, a well-funded food, music and art festival on one of the islands nearer to Bodø, Sandhornøy. Most recently, the

Fleinvaer music centre has taken off in the form of a collaboration with his former (anti) star students, TYIN. Unsurprisingly, water and the ocean are invariably a part of these projects; the ocean inescapably defining the lives of Northern, as much as Western Atlantic Norway. For Rintala however, it goes further. These examples are only the latest in a long thread of projects through which this elemental spirit is threaded; from intertidal water’s edge micro-hotel’s to floating saunas; the expanse and space of Northern Norway balanced with the coast and the sea. Personally too, Rintala is a keen fisherman, and holds more than a casual interest in the culture of boats and boat-building.

Santiago, under the volcano

Photo – Open Source

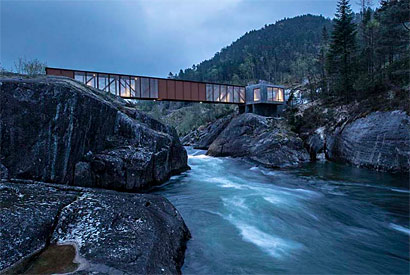

Throughout the time Rintala has been in Bodø, Rintala-Egertsson Arkitur have been preparing one Norwegian or international art inflected, small-scale or slightly larger than small-scale project or another, whether In Norway or internationally. Water flows close to many of these projects. Recently there have been 2011’s Seljord

Look Out points project, a series of boxes angled and stacked edgily upon each other around lake Seljord in the south of the country; two footbridges; the 2013 National Tourist

Route Bru over Høse, a rust steel bridge in the West Norwegian small town of Sand; and in 2015,

Tintra bridge, again in Western Norway. Further afield, the so far only installation on British soil has appeared as part of the Victoria & Albert museum’s

1:1 Architects Build Small Spaces exhibition. The

Book Ark Tower replayed Rintala-Eggertsson’s love of sharply honed, cleanly crafted and well detailed timber structures – adding to the gathering list of long narrow boxy masses both vertical and horizontal, that have emerged from the studio throughout the late naughties and up to the present day. More recently, there’s been the Krumbach

BUS: STOP,

and, along with his commitments to NTNU, workshops spread from Skopje, Macedonia to Sardinia to Chicago.

Miilu pavilion in Venice, 2010, a student workshop built

installation next to the Nordic Pavilion – Photo's Metalocus

If travelling the planet has seemed constant, Rintala’s presence at NTNU has been instrumental in giving traction to the Live Projects culture that has been emerging in Trondheim. The most recent workshop was last autumn, 2016, with boat builder Jan Godal in Valsoyfjord and traditional tools. “It was so quiet” he exclaims. The ten years of workshops and teaching that has been ongoing since moving to Bodø, makes Rintala a hinge between the Atlantic coastal architectural of Trondelag western Norway, and the differently accented northern rim architecture of the Arctic and the country’s High North.

Render of the Bodø Boat Museum, one of Rintala's long sought after dreams – Render Sami Rintala

That Bodø is far from Norway’s mid-region country, is underlined by the seven hundred kilometre, nine hour road or rail journey from Trondheim. Yet it’s another 700 (at least) on to Kirkenes from the town at the end of Norway’s rail line. Flying is faster of course – Rintala can fly to Oslo in two hours. But the sense of distance is still apparent, and easily expanded if Europe, the America’s or Asia are added to the schedule. The last time I had talked with Rintala over the phone in summer 2015, he had complained about the amount of time he’s away traveling. “I was away a hundred days last year.” When I met him last year however, his ideas of figuring out ways of settling down personally, as well as, at least partially, architecturally, had taken several steps forward. “I’m 46 years old,” he said, in the bar we’d retreated to, and he was feeling his age. “After standing on your own two legs, you don’t trust anyone.” Certainly Bodø – at least uptown, has changed since my first brief visit to Rintala in the summer of 2008. Eight years later, the sense of a significant clear-out and clean up of the town’s main grid of streets is apparent. The British architects, DRDH, who won the major downtown library and art house and performance centre project, have helped propel further urban refashioning which, Rintala alerts me to, won 2016’s best urban design in the country.

The waterfront in Bodø, with DRDH’s library and concert hall centre stage

Photo DRDH

The Bodø Jetke Boat Museum – Rendering Sami Rintala

There’s one major project that anchors Rintala to Bodø. This is the Boat Museum, which he’s been tending to on and off the design table since 2011; Workshops and a strong educational element are planned. The museum is his principal or stand out local project, which he envisages as representing (a manifestation of) the boat building tradition; collecting all regional boat building knowledge and information under one roof, while also home to a particular boat type, Jetke. The boat to be displayed – the

Anna Karoline, is sitting on the planned site, too delicate to be moved, waiting for the museum to be built around it. Recently, when I’ve spoken with Rintala, he has expressed impatience at the glacial pace of the project’s progress; which he still isn’t 100% sure is going to happen - or if it does, with him involved. The current state of play is a waiting game. “It would be nice to start, the funding is in place”, he says.

This new stage of staying put was also, or at least partially spurred forward by his participation in Vorarllberg’s small-scale Krumbach BUS:STOP project; where seven international architects were invited to design seven bus stops for the tiny village - “Vorarlberg is just an inspirational thing.” During his Vorarlberg visits, he saw the building culture infrastructure that has developed across the state to support the building. “You have to experience it to understand it. The exhibition was a ticket into Vorarlberg to get to know how it works.” I had imagined the globe-trotting Rintala would have visited many years earlier, but this didn’t turn out to be the case. “It was nice to have a reason to go.”

Rintala-Eggertsson's contribution to the Krumbach BUS:STOP project

Photo's Oliver Lowenstein

Sandane Valley – with forest stands at the head of the fjord from Viking times.

Photo Wikipedia Open Source

Once returned, he began to apply the experience of local timber building culture, to his own part of the world. One strand of thought led him to his own regional fjords; fishing communities and forest stands at the sheltered back of the fjord which had long been planted by fishing communities, a tradition which went back to Viking times. “There are these areas in Northern Norway. They all had their own timber traditions. There are three particularly: Sandane, Åfjord and

Rognan.” The last is forty minutes south of Bodø, close to where the traditional boat builder

Kai Linde, an expatriate German, has been building traditional timber

Saltdal vessels. One hundred years ago, there were 250 boat-builders in the small town, now there’s only Linde. The pine plantations once used for boat building, would be “really viable” for buildings too, Rintala believes; and he has been talking to local timber industry networks about ways to integrate local and regional stands into the regional building culture. How far this will get is another matter.

There are other Norwegian architect’s work, where the old ways and the forest have recently been finding their way back to the foreground of their attention. Skodvin & Jensen’s Børre Skodvin who spent a season learning boat-building three summers ago, comes to mind, and also Rever og Drage’s younger generation Martin Beverfjord. Both with Fleinvaer and his most recent Trondheim workshop, non-industrial, hand-held tools have been the order of the day; and Fleinvaer has used these while focused on designing and making the interiors. Rintala’s NTNU workshop was with Jan Godal, (see the Godal interview with Martin Beverfjord,) each seemingly expressions of a gathering sense that solutions to the climate change crisis are coming from the forests. Not only with wood as a building material, but in the cultures of the forest.

The Salt Fiskhjelle installation on Sandhornøy – Photo SALT

Future forests were a theme Rintala explored at a

2016 Aarhus architecture school talk contrasting the ecological complexity of forests, to industrial society’s emphasis on tending towards monoculture. The forest is both nature and culture, he suggests, while mapping a long view of cultural evolution; history and culture have only been around 3000 years, while the human creature had already spent 2 million years of natural evolution. Architecture, Rintala suggested, is hard-wired into our kind’s biological need for shelter and protection, and for much of our evolutionary journey, forests have provided this long before the emergence of culture, whether sedentary agriculture or ancient city. Doing building originated out of survival. The implication here is that we may need to do survival again today. Survival today and over the next decades, was the point. This long view made sense of Rintala’s nomadic romanticism, from his embrace of fishing and hunting – he said he hunted seals for the Fleinvaer workshop meals – to the backdrop of the namesake Saami tribal culture. Rintala’s evolutionary interpretation of architecture’s role also touches on the ecology of forests systems. Forests, as ecological systems, tend towards complexity as they grow and mature, reaching what’s termed

‘ecological succession’ when a ‘complex community’ is reached and has flattened out into a steady-state. Whether fallen leaf mulch or the many interconnected species, the whole forest is complex and diverse in ways that monoculture’s can’t compete with, and in ways – for human creature’s - that can’t be known. As Rintala noted “you can only experience one part of the forest at a time, you always miss most of the forest.”

You get to the great green Boreal lungs of the North if you head south, or inland and south-east, out of Bodø. North, the forests thin and disappear. The North is another quiver in this bow of new beginnings. Looking north and looking south and inland, melding the future forest to the Arctic, Rintala has begun exploring an Arctic architectural module connected with one or other of the nearer architecture schools he teaches at. Trondheim may be interested, but there’s also Umeå or Oulu. The former is an eight hour, 600 kilometre drive south east to Sweden’s newest architecture school which opened in 2011; the latter, Umea, the most northern university. “Umeå”, Rintala noted in a 2015 Skype conversation, “is cool.”

The vast Northern Boreal forests green lung and Arctic melt – Photo's Wikipedia Open Source

The New North, as it’s been christened by UCLA Geographer Christopher Smith, is at the sharp end of climate change; with weather patterns shifting, the Arctic ocean expanding, polar ice melting and glaciers receding all across this Northern edge. The presence of Industrial cultures is intimately connected to these changes, with both mineral, and offshore oil, rushes in full flow. These two influences are joined by a third: the new North being the main source of another contender for a 21st century’s critical resource – fresh water. Rintala is aware as any that Norway’s wealth and industrial economy, as much as its industrial future, is built on its extractive mining and oil drilling; particularly across its spiny neck of the Arctic rim. With scientific report after report detailing a melting Arctic and so entwined in Climate Change, it is also a locus and symbol of the arrival of the Anthropocene, geology’s new human generated era. For some who’ve embraced the new geological era as reality, such as Tim Morton, philosopher and ‘DJ of the Anthropocene,’ the juncture also marks, at least for humans, a point of no return; a crossing into a state after ‘the end of the world.’ When Rintala talks of survival, he may or may not believe that this threshold has already been crossed. But clues appear present, such as the apocalyptic realm summoned up by hunting and his turn to older hand tools. But even if he doesn’t, Rintala up in Bodø is at the interface of these two connected worlds – the melting hyperobject of the Arctic, in Morton’s framing of the Arctic Ocean, spliced with the complexity and biological wealth of the once and future forests.

The Salt Fiskhjelle installation on Sandhornøy – Photo SALT

“Phenomenologically speaking, global warming does not care about subjectivity,”

Olafur Eliasson, the Icelandic-Danish artist, pointed out after 2011’s Tōhoku earthquake and tsunami, had devastated Fukashima and its nuclear power facilities. “The Japanese tsunami does not care about phenomenology, it did what a tsunami does.” For those who believe that the Anthropocene has arrived, the Arctic is first order and compelling evidence of this new geological epoch. Like a tsunami, the Arctic Ocean cares little for humans. Nor, for that matter, do the Boreal forests. But for humans each are sending different signals. Follow the phenomenological path into the woods and if you live at a crossroads of the sub-polar world, it’s difficult to avoid the confluence of the two; the woods and the water. What, it seems to me, that Rintala can surely not avoid with his new found commitment to staying put, is some form of melding – indeed melting – of the Arctic Ocean and Glacial meltwaters into the forest culture vision that he offered up in Aarhus. Subject melting into object. The phenomenological path crossed with the inexorable – and impersonal – 21st century Arctic reality of Climate Change. Joined to this, a further drop explodes into the Arctic-Boreal forest dynamic – the local, paracentric and global networks that he and Rintala-Eggertsson have made their own.

There is fertile compost here for the nurturing, whether in Trondheim, the high North, the Nordic landmass as a whole, and/or internationally planet-wide. As it is, Rintala our man in Bodø, is perfectly placed if he so cares, to uncover what this New North could be, now that the End of the World is here to stay.

OL