Svartlamoen's ragged glory – Where alt.culture meets avant timber architecture

Trondheim's Svartlamoen district is a living lab for experimental sustainable architecture. Part 1 of this two-part piece looks at Svartlamoen's history and the roots of its avant-community architecture scene, and part 2 – outlines the experiments, which have made it into this unique eco-district.

I

On one of those perfect blue-sky days that can settle over Scandinavia in the summer months for days on end, I walked the short distance north from Trondheim city’s centre to visit the then new kindergarten building with Geir Brandeland which he and his practice partner, Olav Kristoffersen had recently completed. The kindergarten was a rebuild project, housed in what Brendeland told me had been a car sales shop: it was a Saturday and the main entrance doors were locked. As we squinted through the windows at the complex timber geometries inside, round the corner of the kindergarten came five sheep, followed by a young child trying, ineffectively, to round them up. Minutes earlier, the escaped sheep had found their way into the kindergarten’s urban farm area, digging into their midday meal of newly planted flowers. Welcome to Trondheim’s autonomous zone, Svartlamoen.

Born out of a 70’s squat and alternative culture, Svartlamoen has not only survived but thrived; entering into partnership with the city council and collaborating on the masterplan for the whole district - designated an experimental ecological zone - a unique classification in Norway’s urban planning landscape. In Norway and across parts of the wider Nordic world, the story of Svartlamoen, a vibrant social experiment in community living, is well known. In northern Europe and beyond however, there is often surprise that this lost-in-time miniature alt.culture experiment exists at all, let alone that the wider social and community experiment continues to grow.

Svartlamoen Kindergarten – outside

As well as that, Svartlamoen is often recognised for another reason. Alongside the experiments in community living, the heart of the Svartlamoen district has become the centre for a series of eco-architectural and building experimentation, beginning with Brendeland & Kristoffersen (BKArk) first project; a five storey CLT student and affordable housing block and smaller two storey housing building. In part through various serendipities – see the accompanying BKArk piece – the building became something of a minor cult, winning awards and doing the rounds of the world’s architectural media circuit. Not only this, but the Svartlamoen buildings’ success, inspired Stavanger to launch its ‘wood city’ architecture Norwegian Wood programme as part of its 2008 European Capital of Culture. Norwegian Wood put Stavanger on the contemporary timber map. But Svartlamoen was there first.

Brendeland & Kristoffersen student housing block, the tallest CLT

building in Norway at the time of opening, 2005

Gateway to the autonomous zone – Photo Oliver Lowenstein

By the time of this first building project, Svartlamoen had long been part of the city’s urban grain, one of those rare stories where a community managed to hold onto a parcel of city centre land, against the usual story of commercial inner city development. The district mixes wooden terraced housing with its group of experimental buildings which, for some, might be considered messy and down at heel. For others, this literal messy anarchy is part of its charm, although the lack of ordered living is nothing if not a contrast to the gradual makeover of much of Trondheim’s adjoining harbour districts.

“Trondheim is Norway’s rock city,” said the affable Brendeland, one half of Brendeland & Kristoffersen Architects (BKArk) that day. “Like Gothenberg in Sweden, it’s a rebel city. Punk was big here and so was Grunge,” Brendeland continued, explaining why Svartlamoen attracted so many ‘alternative’ types. Brendeland is telling me the story after we’ve made our way to a bar along its main street. Sonic Youth is on the sound system, rather than Royksopp; many of the terraced row of houses around us are painted kaleidoscope colours 70’s style, while posters cover the dilapidated neighbouring walls, and a black flag blows wanly at half mast.

Trondheim's New Harbour (NyHavna ) which

Svartlamoen grew up on the edge of.

Postcard of Strandveien before the new harbour was built .

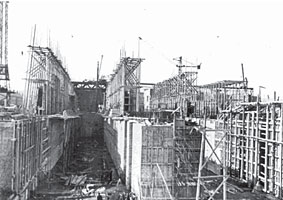

The U Boat bunker, Dora 1 under construction.

These days there’s a strong student representation - the art school is a few blocks west - mixed in with green alt-scene types and neo-punks. The district is sandwiched between two rail lines: the main line running northwards along the back, whlle much of the front faces a second small railway spur siding. Before you get to Svartlamoen, the Strandveiein slip road runs down off from the main cross city artery, and there you negotiate one of those invisible boundary lines; from the larger adjoining neighbourhood, Ladomoen into Svartlamoen - (translating as ‘the dirty Lademoen’), of which it is also a part. In the past, Strandveien – the beach road – ran along the sea front. But as the dockside expanded into the Lade peninsula, the old terraced housing that marks this borderline went up. A short distance further, is BKArk’s kindergarten and housing block - the end of Svartlamoen’s roadside reach. In the early years, the sound of goods clanking and clunking on the siding, apparently put off developers; helping to contribute to Svartlamoen’s escape from the large-scale regeneration of much of the docklands.

Strandveien with the car dealership in the foreground before any building began.

All this is changing though.

Nyhavna (new harbour) the newest part of Trondheim’s docks to face the eco-warriors, is next in line for major development, consultations ongoing through 2016. Svartlamoen’s housing dates from the 1860’s, the terraces becoming home to newly arrived dock and local factory workers and their families as industry arrived in the city throughout the first decades of the twentieth century. World War II and the 1940 German takeover changed this when Trondheim, one of the deepest natural water harbours, became a strategic, and specifically U-Boat naval base. To support its operations, the Germans built two massive concrete U-Boat concrete repair yard and bunkers,

Dora 1 and 2. Built for war, these huge – 16, 000 sq metre - sheds were designed to withstand allied bombs, including three metre thick concrete walls and roof, and sit across from Svartlamoen, dominating the industrial landscape. Huge and undeniably monumental by comparison with their surroundings, the bunkers lend the district a somewhat eerie ambience. Nyhavna fell into decline after the war, and half of Svartlamoen was razed to the ground, although the vast bunkers remained a problem. They were too complicated to demolish, apparently. Dynamiting the thick concrete walls required so much explosive, that there was a risk that a fair part of Trondheim would go in the process, as well. Over recent years, the Dora sheds have been used as festival, concert and exhibition spaces by students, city groups and the university, but the long-term headache of what to do with these symbols of the past remains. Meanwhile, across the road sits Svartlamoen.

Svartlamoen's old terraced housing in summer

Walk round the narrow triangulated patch of land that the eco-district sits on, and you are walking on difference. Some of the housing looks in good order, some is need of repair and care. Though new fire risk regulation at the beginning of the twentieth century required buildings to be built of brick, Svartlamoen’s traditional timber housing is still standing.

Taking on the municipality’s plan to tear down the old buildings - which didn’t meet 1990’s building regulations, in order to preserve this vernacular heritage has become part of the community’s mission. Compared to the houses and housing with their mod cons and heating systems that most Norwegian’s live in, Svartlamoen’s terrace housing were a throw back to an earlier era, but it was this choice the community were arguing for.

Outside, the desire to try out living lightly is equally apparent, as shown in the various built experiments on view. And on the gently rising groundat the back behind the buildings, various patches of the community garden are cared for. It’s scruffy for sure, with all sorts of graffiti art reminding you where you are: a roll call of rock heroes, old school, Zappa and the Stones, some delightful time worn hippy slogans and posters for Svartlamoen’s summer

Eat the Rich rock festival. It’s also peaceful, the untended wild growth of nature left to proliferate round the buildings’ edges come spring and summer. The borders between hard concrete or tarmac surfaces and nature’s rough though soft underside, have collapsed, the lines between the clean and the dirty, blurred. All in marked contrast to the nearest development, the immediate other side of Lademoen, Nedre Elvehavn. A pedestrianised harbour regeneration scheme,

Nedre Elvehavn , though not bad as developments go, bears the hallmarks of consumer-led regeneration found the world over; restaurants, bars, the city’s modern museum, and large supermarkets, but not a weed in site across the hectares of concrete, just another paved paradise. Like so much contemporary development, the public space is exclusively geared to consumption. There’s minimal meanwhile space for just stopping and being, and though a well used cycle route cuts through the harbourside, the signs of slow – unless you’re spending - embedded in its master-planning, are less than zero. Contrast this with Svartlamoen, where you can almost taste the slowness in the air; and where there are small time signs of life all around as well as activity – be it children playing in the kindergarten garden, or the echo of hammering from the self-build which has been going up in Svartlamoen the last two years.

Nedre Elvehavn – Waterways and old docks turned into

residential marina and offices – Photos Oliver Lowenstein

At this moment, Svartlamoen is a child of its times in its unusual planning category. In the later half of the twentieth century, from the seventies and eighties onwards, the local alternative community began to make the modest strip of land and relatively a poor part of town, their own. And over the next two decades, the community grew into an idealistic, anarchist experiment in autonomous community living and organisation. It also attracted, perhaps inevitably, its share of drink and hard drugs. The ongoing

threat of demolition and development brought large-scale protests, and a wave of events and big parties that drew people from all over Scandinavia. Artists, writers, and musicians, including Svartlamon’s house rock band

Motorpsycho, highlighted the situation nationally. It also drew in a particularly well-connected young man.

Petter Olsen, from one of Norway’s richest (and most influential) families. The Oslo based

Olsen shipping magnates family member was involved in environmental work and moved among the country’s art scene. In Trondheim for an exhibition opening, Olsen met some of Svartlamoen’s artists, and before long the hippie billionaire’s son accepted an invitation to that night’s midsummer party. In subsequent months Olsen began supporting Svartlomeon’s attempts to preserve an issue close to his heart, the old vernacular terraced housing. The Olsen story was only one instance of Svartlamoen’s savvy political manoeuvring. Brendeland: “They worked politically right from the start, and they used really clever media tactics.” So, through nationwide – and further – publicity and grass roots activism, by the turn of the millennium the city municipality were backing away from the development agenda. At the same time Svartlamoen’s residents also built bridges to the city municipal planning offices, outlining ways the autonomous zone could be a good thing for Trondheim. By the end of the nineties after years of tussle, the municipality voted to preserve the district for housing and arts activities not, as was originally planned, for industrial development. A Housing Foundation was created to manage the area, with a key planning agreement placing Svartlamoen under a new planning category; ‘an ecological experimental district,’ a first for Norway.

The municipality’s main planning officer in charge was Idar Stower. He remembers: “We finished the plans in autumn 2001. They were complicated, but very interesting and inspiring,” Stower said when I talked with him for another piece over the phone some years ago. “I think we succeeded in this. We both had a common goal of getting a binding “green” plan for the alternative community. The municipality also realised the value of diversity in the city, with places to develop new ideas about dwelling, building and ecological solutions. “There were different opinions about ‘subsidising a strong group’, but the discussions were surprisingly good. I think the success of Svartlamoen is mainly a result of the power, energy and creativity of the young inhabitants, who inspired planners and architects to be more idealistic in their work with

NyHavna's Dora U-Boat bunkers from above, dwarfing Svartlamoen's timber tower

alternative solutions.” In time, the collaboration between municipality and Svartlamoen has been cited in critical planning theory, as another, post-neo-liberal approach to doing community development. However, Svartlamoen’s reach has extended considerably further.

In 2003 a local politician Harold Nilsen, a red-green alliance MP, won the Svartlamoen district seat in the local elections. Working with the Svartlamoen’s community, Nilsen pushed the municipality towards a next step, introducing new, and very different types of buildings into Svartlamoen, to kick off the physical beginnings of this idiosyncratic experiment in ecological urban planning. A competition was organised for a first new project, an affordable housing block, which resulted in submissions from across the country. These included NTNU graduates Brendeland & Kristofferson. Both were working in a sizeable Oslo office at the time, and though confident about their entry, they were surprised when the news came through that they’d won. In the aftermath of the housing block’s completion in 2005, the pair, by now BKArk, continued with the kindergarten and then over the next few years, the reworking fit-out of the interior of the neighbouring warehouse shed, turning it into a recording and rehearsal studio. One way to interpret those first buildings is as alt.culture, or even, punk avant-timber architecture. BKArk was a first chapter, but hardly the end, of this ‘anarchist alt.culture meets youthful green architecture’ story. A slew of art experiments, anchored in sustainability: the kindergarten, further one-off buildings, a completely impressive recycling hub and education centre, as well as an experimental art collective and self-build initiative – have all flowed out of Svartlamoen over the last decade. All realised expressions of that initial desire to become an experimental ecological district.

II

Would the wider world have known any of this if they’d happened upon the swirl of stories, which followed the Svartlamoen CLT five-storey block as it went viral across cyberspace through the summer of 2005? Hollowed out within the image-dominated speed, flux and momentary (in)attention spans of social media, Svartlamoen sat silent, anonymous behind the stock of images that appeared across the world’s architectural media. It made a name for Brendeland and Kristoffersen, just as it obscured how much more depth there was to the Svartlamoen experiment.

What architectural familiarity exists in relation to Svartlamoen, is built on an already decades long story, and one that continues to this day. The latest chapter continues with Nøysom arkitekter’s self-build project, also covered in this Unstructured Extra. As it is, Svartlamoen, at the edge of the Norwegian and the European building sector, has become a site for a series of one-off sustainable experiments that emerged from entirely outside the sectors usual building parameters. And they are seen that way too, Brendeland and others, pointing to how the five-storey CLT housing block wouldn’t have been permitted under Norway’s version of the EU building regulations. It isn’t only that what has been happening at Svartlamoen are a dissenting gesture set against commercial norms, nor that they represent ways of living, working and playing fundamentally at odds with the mainstream’s worldview and mentality. Through the experimental ecological district planning classification, the council green lighted Svartlamoen to become home to a small yet symbolically significant set of counter-examples of what’s increasingly impossible sustainable architecture.

If the housing block, with its huge top floor windows and external rear access staircase, is an experiment in living, BKArk’s second Svartlamoen project, the kindergarten is another experiment, this time, in learning. Based on the Emilio Reggio educational pedagogy, the kindergarten grew alongside a parallel Reggio project that has flowered at Svartlamoen. Tucked round the back of Svartlamoen the ReMida and reuse centre, is one of best equipped and most thorough recycling culture educational environments I’ve come across. Together with the kindergarten ReMida adds a practical and established social and educational philosophical dimension to the wider urban ecological experiment.

Brendeland & Kristoffersen's kindergarten

Photo Pasi Aalto

The Kindergarten in 2015 – Photo Oliver Lowenstein

Run by Ann Sylvie Olsen who’d long been teaching at the old intermediate school attended by many of the district’s children, the kindergarten began life in meetings with Svartlamoen residents. “Between ten and fifteen would usually come,” Olsen recounted, on one of my visits. “They’d come and they’d go. At times some weren’t altogether reliable. At first I’d get annoyed, and thought they should all be at the meetings regularly, but then I realised that when I was at a municipality or school meeting with 50 people, they’d have to be there, and half would be asleep,” she says, amused. “Participation, from the Reggio approach, is a very important part of the philosophy. Everybody is involved, including the children; it’s truly democratic.” The result that’s gradually emerged, talked out meeting by meeting, was surprising to Brendeland. The community decided to put the classrooms at the front with open windows to the world. “Geir was really shocked,” Ann Sylvie Olsen remembers, “not completely surprisingly” - as it went against the grain of contemporary school building design. They also decided to put an open crossing ‘piazza’ area in the middle of the old showroom. “Including the Italian piazza, where people meet, was very important to the Svartlamoen parents,” she continued. “Everyone has to cross the piazza to get to

Point Grande's Europan 10 Svartlamoen project

other parts of the kindergarten. So we have to look everyone in the eye, something we shy Norwegians don’t like.” Olsen says yes, the warm timber walls of the kindergarten rooms, is partly an educational resource, although other materials, important for tacit learning are also significant, part of the developmental approach the kindergarten uses. Dividing up each of these rooms are completely one-off massive wood (CLT) walls. Their strangely disorienting shapes seemingly splay off in different crazy paving directions. The prefabricated engineered timber has produced some lovely shapes, so very different to much modern school design; slanted walls and a buoyant irregularity immediately reminding you of the natural anarchy of small children, as well as the immediate neighbourhood beyond the open windowed walls.

Completed in 2008, the kindergarten is one of Svartlamoen’s social meeting crossroads, young parents hanging out in and around its entrance. There’s no high security fencing or walls, a reminder of how much less paranoid the built fabric of alternative cultural experiments invariably are, though also of the pressure drop found across the Nordic world compared with that of Anglo-America. Round to the side is the urban farm, and at least on my earlier visits, the feral goats, as well as other live-stock.

By the time of the kindergarten opened, plans were well advanced for a second young practice led project to continue what had begun with BKArk CLT housing block. Municipality and Svartlamoen members working together within the Housing Foundation had enabled Svartlamon to be included in one of the Nordic sites in the EU’s

annual Europan competition, in 2010. The housing group prepared an extensive brief for a mixed use building on Strandveien, designed to also connect to the submarine bunker across the road and the railway no-man’s land. Won by young, primarily Greek, students, Point Supreme Architects www.pointsupreme.com, their design developed further over the next two years, but then appears to have run out of steam; the momentum slowing before quietly fading away. How far the Europan entry would have continued the CLT experimentation is now moot. But as the last municipality supported project to date, one result has been that all subsequent projects initiated since, have been undertaken by Svartlamoen residents; all are considerably smaller and have circled around low tech, re-use and recycling themes.

ReMida – Svartlamoen's one-off re-use centre – Photo Oliver Lowenstein

ReMida, although not a building project, was one of the starting points for this homegrown direction. Round to the back of the kindergarten, ReMida uses up a full half of its converted warehouse/shed home. The name comes from King Midas, alluding to how the centre ‘remidases’ base worthless materials into things of golden value. Run for several years by Pål Bøyesen, the spectrum to be uncovered in this re-usable treasure trove is a delight to the imagination and inspirational in its very existence. There are serious shelf-loads of variously sourced materials, which have arrived from equally varying parts of the city. A tin can robot stands on one side, and boxes and boxes of spare parts - are used for self-build Meccano or other constructions, on the other. There’s a developmental emphasis on forms and shapes for young minds and hands to get to imaginative grips with. Considerable amounts of plastic in a bright colourfield of primary blues, yellows and reds jump out at the eye. Constructed out of old window frames is a glass-space within the space, it is surely a prototype for the pop-up window-frame gallery space that the art-collective who run the other half of the warehouse, Rake, built in 2013. For someone from austerity hit Britain, ReMida, which receives municipal funding, seems like an embarrassment of re-usable riches, even when Svartlamoen folks talk of how it’s been hit by cuts in the city’s commune budgets.

Rake's studio with the Stavneblokka timber-brick project still in place

Photo Oliver Lowenstein

Rake – Windows On

Rake, the next door tenants, began life as a two person artist-architect collective and is the result of a meeting between students Trygve Ohren and Charlotte Rostad; who – through the summer of 2012 and with friends and peers, jointly created the first project, a temporary art space, made from the aforementioned salvaged window frames. Their Rake gallery created an art-room of their own in which to show their work and, initially for the first months, produce installations and performances. Rake’s gallery happened at a propitious moment in Trondheim. With a wave of young art students graduating who, instead of heading south to Oslo as had been the norm, continued to live and and work in the city. This created a small youthful, innocently enthused art scene whose members needed a place to show their work, and Rake were on hand with the answer. That scene morphed and cross-hatched with the Live Projects architectural students projects over the next few years. Conceived by the architect half of the Rake’s two-some Trygve Ohren, for a couple of years the completed Rake art-space provides an early illustration of this cross-disciplinary practice across town, its outer façade made entirely out of window frames, its interior a forest of wood blocks. These days it is still hosting exhibitions and events, although it has moved to new temporary grounds, the port side of the main rail station. Awareness of the art-space spread wide and far, including to some unlikely organisations. In 2014 Ohren and Rostad were both stunned at the news that it’d was a runner up short list nominee in the EU-sponsored 2013 Mies der Rohe European architectural awards.

Winter work on the Self Build – Photo Vigdis Haugtrø

At the time, neither were directly involved in Svartlamoen, but by 2014 the couple had taken over running the empty half of the ReMida warehouse, with a half dozen other artists, most of them eco-district residents. The room was also used to construct and test one of the Stavneblokka recycled wood brick designs; and in 2015 Ohren and Rostad moved into Svartlamoen themselves. By then, Ohren had gravitated towards community architecture and was helping propel the self-build project that is nearly completed across the car park area in front of the ReMida/Rake shed. Whatever the radicalism of the NTNU’s live projects –

discussed at length here by Steffan Wellinger and co – Nøysom’s self-build project makes for a vivid contrast to the next steps of most of the other NTNU architecture graduates; overwhelmingly drawn into joining the mainstream of Norway’s architecture, rather than heading into the community activist realms of Svartlamoen. When asked if he considers himself an activist, Ohren replies that if being more interested in simple building systems, and “the relationship between people and their understanding of the built environment is activist,” then, yes, he could see himself being described as such. Involved earlier in social work Prior to applying to NTNU, Ohren was involved in social work, and it has led him back to the earlier generation of pioneering community architects; including Rolf Jakobsen and an original member of the Gaia Architecture Network, the influence of which have been instrumental in setting out on the self-build project which consumed Ohren’s post-graduate work and has continued to do so since.

Proximity to Trondheim’s art school is perhaps a partial explanation to Svartlamoen replenishing itself with younger, animated and wilder artist types. Moving in for longer or shorter periods of time, some moving on, others putting down longer-term roots, during their time in and around the eco-district, something new will often take shape; appearing rough, ready and makeshift, and far from the faux-sophistication of the metropolitan white cube art-worlds, to further populate the small stretch of land. The Husly project is a case in point.

Vigdis Haugtrø’s Husly’s pallet self-build project– Photo’s Vigdis Haugtrø

was really the only other new building in Svartlamoen, until Ohren and his colleague’s self-build began on site in 2015. New is misleading, since, like Rake, Husly has re-use at its heart. Part of a wider art project in 2007

Generator, Husly – (translating as ‘shelter’), was conceived and completed by artists

Vigdis Haugtrø and Jan de Gier. Rather than window frames, Haugtrø and de Gier began with an equally everyday material common-place, the pallet. Posing the question to themselves of what was possible with Euro-pallets, Haugtrø and de Gier investigation explored the meanings of house and home, and dependence and independence within and outside the market place. In practical terms, the pair collected pallets and began making a sheltering home out of this basic raw material over the summer months. The resulting home also sought autonomy from energy dependence; a woodstove was integrated, wind turbines were mounted on the roof, likewise an experimental toilet. Once completed, Husiy sat at one edge of the harbour-front through the summer. Haugtrø was living in Svartlamoen and in September the pallet home was lifted onto a boat and transported across the harbour, before being moved onto a reserved patch of land between the housing block and kindergarten. There it was repurposed into a guest bnb for visitors, including bands coming to rehearse and record in the music studios. Haugtrø lived there for a while, continuing other art work – with a number of collaborations with Sami Rintala - before moving to the countryside in 2015.

Two of Svartlamoen's artist and resident Per Kristian Nygård's works - Left The Garden,

right Not Red but Green

Rubik Curve

Art-appropriation of the everyday turns up repeatedly. The far side of the housing block is Swedish re-use artist,

Michael Johansson’s Rubik Curve eighteen multi-coloured repurposed blocks of one metre square chromatic metal, brings bright colour to the edges of the district, running the edge of a curving wall, arguably a structural as much as installation piece. There are other artists working with structural building themes as well;

Per Kristian Nygård has developed a part of his practice around absurdities and surrealisms in the built environment. For apiece commissioned by Rake,

The Garden,

Nygård crammed a garden into a second floor flat in 2014. A year later a wilder outgrowth,

Not Red But Green, pushed and poured out of another series of rooms, this time in an Oslo art-space. Outsize, obsessive model made cardboard tenement blocks were presented to Stockholm subway riders, standing on the Odenplan metro platform through 2011, while another work developed a home for a separated family, with separate entrances and rooms for each of its members, spatially reworked to account for who was and who wasn’t talking to each other amidst the fallout flux of family relationships. They are lovely, if sad, commentaries on one aspect of the realities of housing that one can’t help feeling commercial house builders, whether sustainable or otherwise, haven’t even considered, let alone considered building. That’s the kind of place Svartlamoen is, asking questions of what the built environment might be if the imagination of the artist was set loose.

Local Trondheim politicians celebrating Svartlamoen's self build ground breaking

Photo Siri Gjerje

Buildings, sustainability, and the overlay between social autonomy and sympathetic architects have turned Svartlamoen into a one off, off-road and metaphorically off-grid, living lab. With its two experimental building trajectories, BKArk’s early CLT phase, and particularly the low tech, re-use chapter, there’s a considerable spectrum of potentially inspirational work for others wanting to draw sustainable architecture and building culture into the field of living social and community experiments. The prospect of further experiments exploring both strands in single projects is provocative, particularly as building material re-use is beginning to crossover into mainstream agendas. Svartlamoen after all has much to highlight and to share. Though I can’t be certain, this unlikely fusion, of the contemporary youthful architectural edges mixed in amidst self-build and other experiments just do not exist at such a developed level anywhere else in Europe.

Bristol’s Ashley Vale could be considered similar, but doesn’t contain a comparable experimental avantarchitectural dimension. One might well cite CAT, Vauban, or Christiana in Copenhagen, but again the balance is one-sided and weighted towards self-build, ignoring the architectural, or where it exists the work of older generations – David Lea’s work at CAT comes to mind. If there’s something gently protected about Svartlomoen up on the faraway shores of one of Scandinavia’s social democracies, arguably an expression of the Nordic world’s social and cultural tendencies to look for consensual solutions, this doesn’t underscore what’s happened there. Perhaps every town and city should have its own architecture of dissent.

At present Svartlamoen’s future seems uncertain again. Though Trondheim municipality support Svartlamoen, lack of funding is, as with many such set ups, ever present. With Nyhavna again on the table for development, concern about the future was in the air when I last visited in 2016. The university are becoming more involved in various Nyhavna initiatives, and the latest Europan 13 used the site again as part of its call-out. Talk to some in Trondheim’s small architecture scene and one isn’t short of people who are speculating about the possibilities of what Nyhavna could become. But one look in the rear view mirror and what has so far unfolded on the main ex-dockside site, can undercut optimistic words. When the time comes Svartlamoen may be swallowed up whole into Nyhavna. There again, Svartlamoen’s identity is built on its having successfully taken on the mainstream, surely enough to temper all out pessimism.

Two faces of Nyhavna – a stored trawler

against Dora 2’s wall and

after a midsummer festival. Photo’s Oliver Lowenstien

The ‘nøysom’ in Nøysom arkitekter translates as frugal. It’s an apt description for these simple, lo tech, accessible and homegrown architectural experiments. As a counter-pole (

counterweight?) to the increasingly tech dependent, BIM enhanced, technocratic and regulation led architectural and building landscape, exposure and experience of these counter-fields are only becoming more marked. Like the older vernacular terraced housing, Husly’s pallet home, Rake’s window frame art space, ReMida represent another left field vector to the more polite, domesticated student-led Trondheim Live Projects, for those relaxed about a walk on the wilder side of the tracks. Frugality is a synoptic commentary on the mainstream’s tendencies to excess, both generally and when it comes to building culture, even if both the centre and Svartlamoen’s point at the edge are contrasting expressions of Nordic Lutheran ‘frugal’ reserve and restraint. In a world of mind-boggling inequality, the fusion of different strains of building and materials re-use, alongside the current ongoing self-build, with its social and community experiments – illustrates what can still flower in environments where the empowering potential of autonomy finds a space to exist. To find living labs with small groups of people exploring what autonomy, agency and a degree of control over the future are rare enough. To come across a place like Svartlamoen, which expands on this experiment in freedom to embrace an authentically architectural and building culture dimension is even rarer. It needs tending. These small building gestures may not be glamorous nor stand out in the crowd. But though few in number, Svartlampoen offers a way into building, and building reuse in community, which – given the momentum across building production of moving ever further from building simply and ‘on the ground’, is in dire need of representation. Svartlamoen, a singular ragged glory remnant of its alternative culture roots, does that, quietly and with love and care.

As we walked along Strandveien that day Brendeland said something, which stuck in my mind over the years. “They stole a part of the city and got away with it.” Whether true or not, I couldn’t help but feel this small community had given back and shared quite enough.