After Weald & Downland:

The next chapter in Cullinan's timber path

After the Weald and Downland gridshell, its architects pursued serial other timber experiments. None of these saw the light of day, until Inverleith Botanic Gardens visitor centre opened, complete with its floating diagonal grid canopy, in 2010. In the years leading up to this new building, Cullinan's explored another shell structure; lamellas. Here the practices follow up timber chapter to the W&D gridshell is told in full.

All Inverleith Botanics Garden visitor centre photo's: George Sinclair

except where credited otherwise.

Actually, the visitor centre is long and flattish, what the architectural world call horizontal, breaking the downward sweep of a slope and basin all heading towards the old gates main entrance. To the buildings right, from inside the gardens, there’s been much done with slate, indeed what I realise is a room reaching underground into the side of the gardens ground, provides an opportunity for a long, long slate wall sinking down to the glass vestibule foyer way-in/way out. The wall states, at least to me, ‘back country sustainable’ – remote rural, hill walking and dry stone wall imagery It’s already cleverly deployed by young Scottish star,

Gareth Hoskins , on his northerly

Culloden battle visitor centre outside Inverness. Here, at Inverleith, with added vertical slitted windows the feel is half-Hoskins and half reminiscent of some latter day medieval fortification. The length and smoothness of its deepening line distracts the mind from thoughts of dour rain-sodden Celtic fringe towns.

Past along the slate the path slopes down to the far entrance, the glass vestibule area, with, on its outer edge a cylindrical boiler-house also wrapped in slate. Handsome. If you’ve arrived from the road that runs around the botanic gardens perimeter hedge this glass atrium is also the way in, past the arches on one side, with garden views of what’s to come ahead – and in the foyers middle, a rather lonesome palm tree inside a funny boat-shaped cup of earth.

By this time, for road-bound arrivee’s, the visitor centre’s outward roadside face has already presented itself, with, first on the southern facades approach, an Aalto-esque curve and woody façade, three rows of deep red vertical cladding, which thus far haven’t weathered away from its rich autumnal, woody reds. The relative gentleness of the curving wall, may seem old fashioned, almost Modernist art nouveau, with eco-add on, though such contemporary curves can be seen all over Europe, if not dominantly, often enough. Between this woody end and the far slate stone and glass north-eastern end, a busy and high hedge has been kept intact, and obscures a small plant and garden area of the retail operation, covered by a set of marquee tents. The two contrasting end-pieces – wood façade and slate plus glass respectively, suggests a busy entity. Pass the foyer and then through the swinging doors, and something of this disappears. Inside the logic of the internal space takes over.

Immediately the other side of the doorway the spacious open-plan ground floor spreads out in front of you. Near its centre the ceiling melts away, opening up to the second or upper floor and sunlight, streaming – on a good day - through roof-lights. Before the inner atrium spread, and on the right is ticketing, followed by open plan retail, while to the immediate left is a gallery and exhibition space. Three long and thick – almost a metre deep - glue laminated beams sitting on comparably slender steel pillars, recede into the gallery. This is the accessible part of the underground building dug into the side of the gardens rising topography; the glulam making long parallel lines - a vista of 3D geometries. The thin columns are a complimentary brown to the lighter glulam hue.

The glulam continues, though shorter in length, beyond the open atrium until the end at the far wall, and doorways into offices and other administrative rooms. The edges of the gallery curve round to meet a science area hived off, across to the far opposite side of the entrance. In the open centre is a tree, rising up so its canopy is level with the upper floor. At the far end a slinky, stylish timber staircase, connects ground with the upper floor restaurant and the exits onto an open patio. Climb the helix shaped stairs, another botanical form of life, which the Botanics team were apparently particularly keen on and you are soon out again onto the boardwalk decking curving round the landscaped pond, and views up into the gardens proper.

If so far as the most striking external element has been the slate walled entrance approach and foyer area, inside its timber, which takes over. The interior highlight and quasi-wow excitement, as far as the building internal spaces are concerned, are the four way butterfly or propeller wings, glulam again, sitting above the restaurant and the rest of the upper floor. Supported by eight columns, the canopy system is an adapted diagonal grid to be filed under exotic roof structures and plays to Cullinans exotic roof structures reputation, even if the reputation is based on very few actually completed buildings. It sits there, almost levitating, quietly, its significance underplayed, and by many eating in the restaurant, unknown.

-----------

In fact this elegant diagonal grid represents a conclusion of sorts to a particular journey in Edward Cullinan Architects history – an eight-year odyssey that fills a next chapter, an answer to the ‘what next’ question that was brought on by the remarkable popularity and success of the 2002 Weald & Downland Open Air museum gridshell. Certainly within a certain section of the architectural world there was a sense of anticipation for a follow-up to the W&D gridshell. What did happen next on Cullinan’s timber path turned into a long, open ended, though absorbing, trajectory of tracks started but not eventually taken, until Inverleith botanics could be said to be in the home run.

Although known for a socially-minded approach focused on public sector buildings, ranging from schools, health centres, through to HE buildings, and housing, there was a strain within the North London based Cullinans that projected consistent interest in projects involving rural settings and related to the natural world. Up to Inverleith this strand was represented by two experimental buildings; Weald & Downland, and the two earlier primitivist, roundwood projects at the

Hooke Park furniture school in Dorset. Both were deep in the countryside, rural in ethos and in their design approach. Nine years later Inverleith represents the first full realisation of a related if different profile of buildings, this time connected to botanic gardens, partial complements to those earlier exercises in rural culture. In the intervening period Cullinans made a sustained attempt to extend their range of timber canopy structures, with one project introducing the practice into the world of botanical gardens and providing the entrée into the Edinburgh botanic garden project.

Downland Gridshell (Photo: Katherine Rose)

Cullinan's Hooke Park's Westminster lodge (Photo: ECA)

A second consistent factor throughout this unfolding timber journey, from Hooke Park up to Inverleith, has been the partnership with Bath engineers,

Buro Happold. Indeed it’s been Buro Happold who introduced Cullinans to many of these forms and building types. Winning the limited competition in 2005 – against the likes of

Wilkinson Eyre,

Page & Park, and

Michael Hopkins, and

Richard Murphy Inverleith provided another opportunity to work with Happolds. It also allowed the Cullinan’s team, led by Edinburgh native, Roddy Langmuir, to draw together a bundle of ideas, which within six months had firmed up into a definite conceptual design. The Happold link had originally been initiated at Hooke Park, and solidified during the W&D gridshell work into a shared team approach and understanding, after W&D had provided a systematic fusion of original research. Years later, this teamwork would feed into Inverleith, and the considerably more complicated initial roof structure. The early design envisaged a rippling wave-like form, with a series of clerestories, providing natural lighting to the main heart of the building. A version of the timber butterfly wings was already envisaged, structurally supporting the roof. This design was prepared as part of a large Heritage lottery funding application by the botanic gardens. The bid went ahead but was unsuccessful, putting any next stages on ice until funding could be raised, which in the event was a full year.

(Photo: Paul Raftery)

A year on, as 2006 moved towards 2007, the botanic gardens had resolved the funding difficulties, and Langmuir began looking at the design again. By then, for him, the roof felt too busy and needed to be simplified. A simpler and also flat roof would also bring down the cost, as well as draw out a certain calmness, particularly as much of the rest of the buildings expressiveness took its lead from the roof. “There was so much going on, and I was seeking the delight in it.” A decision was also made to design using massive wood, a first for Cullinans, with the Austrian company,

KLH brought in to supply their cross laminated panels for the walls, floors, and roofs. The introduction to working with the new and increasingly popular engineered timber material was significant for the practice, providing experience and familiarity. They have gone on to specify clt panels for subsequent projects, such as the

East London Institute of Sustainability.

Still in terms of Cullinan’s history, it was the timber roof system, which Langmuir would eventually arrive at, the adapted diagonal grid canopy, which remains the most interesting timber feature at Inverleith. Covering an area of about 100 m by 50 m, the grid was composed of 8 x 6 m tapered glulam beams that create, looked at from below, a latticed diamond effect of the four way butterfly wings. Where each set of four glulam beams meet, they are joined to a vertical rod by flitch plates, with the rods transferring the loads being carried by the diagrid down onto long slender fluted steel columns, narrowing from a comparatively wide 1035 mm’s at their heads, to just 300 mm’s as they reach the ground floor. (For a clear technical overview see the

Trada case study.)

“We had a lot of arguments over the columns” says Langmuir now, on how the slender steel columns were reconciled together and integrated with the thicker glulam system. Essentially a kit system, the glulam’s were tapered and then screwed into the connecting steel plate, the screw plates making a circular pattern at the end of each of the glulam’s, a simple and economic way for realising the visually dramatic canopy. “As a metaphor it’s fairly obvious – a forest canopy amidst the upper branches of the building.” Put up by DonaldsonMcDonell a Scottish timber-framer, (for whom this would be their last job as they went out of business soon afterwards,) Langmuir is adamant that it was an economic option. “The roof wasn’t expensive; the timber budget involved a lot of effort, design and work.” Still £16 million - about 3300 per sq m – is not an insubstantial amount, Inverleith required serious money. The clt panelling on the floors, walls and roof add to the overall timber feel of

the building, as does the external cladding. The helical staircase and other furniture detailing also added to the overall timber budget. The investment is being made back, apparently, in different ways. On the southern restaurant is a private dining and functions room, self-importantly titled the David Douglas room. The winter day I was there I asked one of the restaurant staff what it was like working there, and she said she liked it. “It’s good to see daylight” came the reply, between busily preparing a table.

Outside, beyond the glass curtain wall and butterfly wings supporting the external overhang onto the patio, is the corten wall curling round the pond and into its surrounding layered landscaped garden. On the building’s South West edge a series of steps fall away from the decking, to make a patio stage space, for outdoor performances during balmier weather. The open theatre is again a mix of corten rust and timber clad open-air seating. Although a contrast to buildings with one dominant material, the splash of timber, slate and corten, plus its various eco-bling does at times give off something of a feel of a kitchen-sink full of eco features had being thrown at it, and left me wondering what the original design was like, before the decision to simplify. While the slate wall is calming as much as dramatic, the corten-fencing round the pond edge adds a second material element into the mix, further supplemented by the curving glass curtain and glulam butterfly wings, while over all this, the sedum and

Quiet Revolution micro-turbines on the roof. There is also the pond and the landscaping to take in. Still aspects of this materials palette is softened by the scale, even if, yes, at times I found the visitor centre large and slightly overwhelming, though not overbearing. I smiled when remembering my friends words about how the building might be confused for an upmarket service station, though felt there was considerably more to it, than such a remark, even when made in mirth, might imply. Part of this must relate to the ecology and environment interpretation brief relating the gardens to bigger planetary pictures. Environment, ecology and for that matter, education, were also, in differing ways, a significant strand in the story at both Hooke and W&D. Here, however, is Cullinan’s first realised attempt to do so in the rather different, essentially public and urban, arena of a botanic garden.

How opaque is the connection between the two strands? Distinctively rural and raw, somehow, on the one hand, more urban, cultivated on the other. Or just a matter of history, and different building types? One interpretative schema would view Inverleith as indirect descendent and continuation of a path begun with Hooke Park and W&D. This trajectory partially depends on including

Savill Gardens, not a Cullinans building, but that of Glen Howells Architects , and a much flashier, slick update of the Weald & Downland’s primitivist gridshell, as the link between the latter’s rural flavour and that of botanic and garden centred typologies. Just as important, perhaps, to such an interpretation were two projects, both involving linking sustainability and the environment to a particular interpretive building, though ones which would never see the light of day.

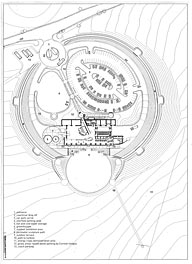

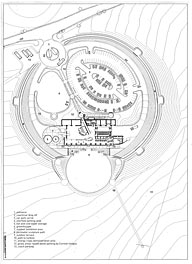

Gaia Renewables Centre plan

(Plan: ECA)

The first of these was the

Gaia Renewables Centre sited along a part of the North Cornish coast that had hitherto been immune to tourism, just outside the slate quarry and impoverished village of Delabole. The Gaia Centre was the brain-child of

Peter Edwards, an energetic North Cornwall landed farmer who, presciently, gave over some of his farm land for the first wind farm in Britain. Opened in the last month of 1991 the wind-farm’s ten turbines were quickly producing four mw’s of energy for the immediate neighbouring communities. Not completely surprisingly this renewables first brought this out of the way bit of the Cornish peninsula a steady flow of tourists coming to gawp at the high rising turbines. The idea of an interpretation centre followed on naturally enough from this. Initial funding through Cornwall’s then big

Objective One grant from the EU, plus a

Thermie renewables grant and other national and regional Government sources, Cullinan’s were taken on in 1999 to develop a design, which highlighted environmental and renewable energy. It was half way through the Weald & Downland gridshell design, and Cullinan’s were keen to explore other timber structural techniques. What they decided on, a timber structure known as a lamella, emanated, as with the gridshell, from the German timber engineering tradition. Unlike the seventies

Frei Otto light weight structures, however, the lamella was from a more distant era, the interwar period, and was known only to a few wood specialists in Britain, including Buro Happold’s then head of timber engineering, Richard Harris. It was through Harris, who’d also been at the heart of the W&D gridshell research, that Langmuir and others at Cullinans were introduced to the building technique, a diamond lattice form of construction built up from small regular pieces of wood. “I had no idea what a lamella was”, says Langmuir of his introduction, but could see that the wide spans that structural technique could cover, would fit the Gaia Centre project well, which he was also project architect on. It also fitted the requirement of a much stronger roof, including a planned photovoltaic array, than any lightweight gridshell could muster. “We wanted to do a single long span that would be able to carry quite a load.”

Zollinger Lamella Merseberg (Open Source)

Hugo Haering, Gut Garkau

(Open Source: Seier & Seier)

As Langmuir began looking into the history of lamella’s he would have uncovered its origins in the 1920’s, and its particular identification with one

Friedrich Zollinger. Zollinger, (1880 – 1945) who trained as an architect and engineer - and from 1918 onwards was city architect in Merseberg, N Germany - is credited with developing his patented Zollinger lamella design, as part of a cheap and quick building method for roofing housing in the immediate post World War 1 period. His lamella decks emphasised small timber sections for forming near curving barrel arches with the material result that many were built across Germany, particularly in and around Merseberg. Having founded the Merseberg Building Company in 1922, over the following years Zollinger expanded the timber technique to be applied on schools, churches and large halls. Other architects also took up lamella’s including the experimental Berlin architect

Hugo Häring, also a forerunner of the twentieth century organic building tradition. His Gut Gatkau farm barn, designed for an experimental community in North Germany, continues to be considered a critical part of

the other Modernist tradition with Häring viewed as a forerunner to the likes of Utzon, Schareen and Aalto.

In the aftermath of the German experiments lamella designs as economic solutions for spanning large spaces began to come into their own, migrating to the States. In 1927 one of the largest Zollinger lamella’s went up to house an arena in St Louis, Missouri, while through the 1930’s a number of aircraft hangars were constructed, though as timber fell from favour and twentieth-century materials such as concrete and steel took precedence the lamella option became rarer and rarer.

GAIA Renewables Centre Lamella Model

Cullinans were thus attempting to revive in contemporary sustainable form a one-time successful timber structural approach. At the Gaia Centre the lamella roof also needed to be strong enough to carry various features suspended from the ceiling, which given the lamella’s rigid and diagonal form was a further mark in its favour. Langmuir also envisaged the expressed canopy complementing the slate-wall planned for the back of the building, while also working with the rising 25 degree angle at the front, to effectively carry the solar array. Langmuir liked the simplicity of this engineered approach, more systematic and constructed from regular pieces, rather than a jigged up frame. “What”, he notes, “is complicated is how to end the section, ie, how to cut off a lamella, a system, which is set up to go on forever. “When you cut that off you terminate at the end of the bay, which is therefore pushed back through the closing beams at end.” The plan was for a broad grid to form the trusses, which the PV array and other renewables would sit on. Cullinans were also envisaging that the lamella would highlight locally sourced wood.

However by this time, funding began to run dry, and with the centre’s sustainable attractions dependent on funding for the research, the project began to slip away from the architects. What was left was some early ground-works, a big semi circular ring awaiting the lamella and a construction start date. For Cullinans the project was over. Eventually, a minimal budget was secured for a local architect to be brought in to put up, in Langmuir’s words, “a big shed”. Before that, during the early ‘waiting for funding to materialise’ period, a ‘charming and amateur’ exhibition set in two temporary portacabins was visited by, Langumir states, 30, 000 people. That must have been a hopeful sign, particularly as the business plan gave a figure of 150, 000 annual visitors. In the event, after opening in 2001 less than one tenth that number ventured up to Delabole, the big shed and the windfarm. Langmuir partially attributes the low numbers to a ‘very poor exhibition’ and within three years the Gaia Renewables visitor centre closed its doors at the end of the tourist season in October 2004. By then the lamella structure was already long a ghost idea for an environmental interpretation centre, the concept of which was itself probably ten years ahead of its time.

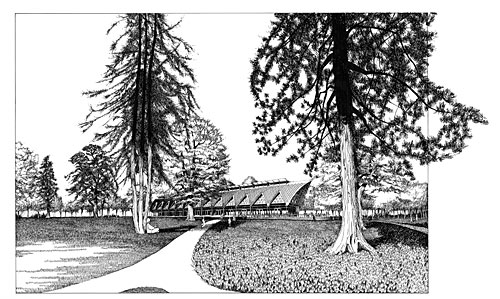

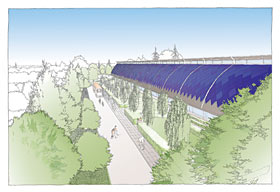

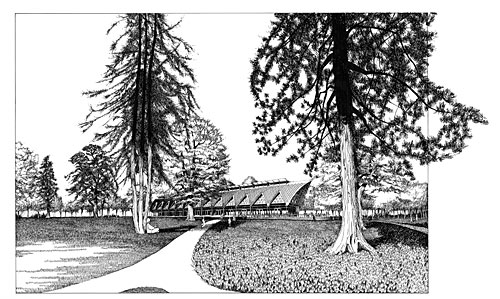

Cambridge Botanics Visitor centre (Drawing: ECA)

Meanwhile during the same time period, and for a while running almost jointly and alongside the Renewables Centre, was a second timber lamella project within the Cullinan studios. Once again the focus was on an interpretation and learning centre, though this time in the heart of a university city, Cambridge, and for the

University of Cambridge University Botanical Gardens.

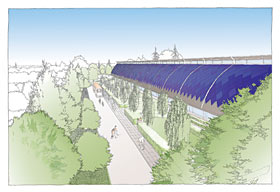

The eventual form that ECA arrived at Cambridge was determined by the size and length of the proposed building. Initially during the early contact between Cullinans and professor John Porter, the Botanic Garden staff figure overseeing the visitor centre project, there was a real interest in seeing how a gridshell could potentially be designed for this rather different context. Quite quickly, however, it became clear that the functions the envisaged building was to be used for, were too complicated for applying the gridshell form. With all year round visitors the building would need both insulation and working windows. A gridshell with its tendency to shift and move over time, and its lack of rigidity couldn’t deliver this, and the two Cullinans architects working on the project, Carol Costello and Johnny Winter, began to consider the lamella option. “At the time the two projects were running simultaneously,” recalls Costello today, a decade later. There were very particular demands the Cambridge building needed to meet, not least a large open space. The design arrived at were two separate lamellas, which came together at a mid-point. Together the two parts made for a very long building, Costello referencing Indonesian longhouses. Working once again with Buro Happold’s Richard Harris and his Bath team as well as the timber structural engineer,

Gordon Cowley, a design developed which would utilise literally tens of thousands of very small, 1.2 m by 2.4 m lengths of low grade wood, together comprising the diamond lattice shape of the lamella.

Cambridge Botanics Visitor centre (Image: ECA)

However, as the centre needed to be insulated from the elements, this diamond lattice was also to be covered with a further façade. Cullinans, who took the project to stage C, considered various options; glass, cedar shingle cladding on one side and a PV wall on the other, south, side, and also ETFE foil. Not only this, but inside the diamond’s the design integrated the ventilation windows. All in all the building would extend about 90 metres in length.

Inside the buildings needs were equally complicated. Under the lamella canopy would be a heightened first floor, while underneath was an understorey, where toilets, ticketing and other more ‘mundane’ parts of the centre would be situated. The upper storey was the glamour area, featuring a café, conference centre and a staircase walk showing off the timber roof canopy to best effect. This part of the concept worked well, as big spaces needing covering in a single large span are exactly the kind of thing gridshells and lamellas are particularly suited to. Where they become less effective, and visually less dramatic, is if and as the internal space is broken up and divided into separate bays, so that the sense of space disappears. This is what began to happen next with the Cambridge lamella. “It was pushing the brief, and some of it was slightly contrived. If you weren’t considering a lamella, you might well have considered another type of building,” remarks Costello now.

As it was, while Costello and Winter spent many months on the project, it stalled when the serious push for funding came, and by 2003 with the Gaia Centre already out of the picture, Cullinans experiment with lamella’s was over.

East Hounslow Station Lamella

(Photo: Open source)

PetzinkaPink Lamella

(Photo:

PetzinkaPink)

Buildings which don’t materialise are hardly big news stories in architectureland, rather lost footnotes of paths not taken. Still, if either of these two visitor type centre’s had been completed Cullinans would have introduced to the British architectural world - by way of Buro Happold’s benign influence - another timber structural building type. As it was Cullinan’s interest was part of a small-scale turn of the millennium resurgence of interest in the form. In London Acanthus Architects used two lamellas for the upper platform segment of their re-design of Hounslow East Undergound station. Rising up from the entry and ticketing at ground level the lamella canopies sit on tree like beams, with the roof deck dressed in a copper skin. The renewed station was re-opened in 2004 after Cullinans had wound down its lamella work. Not dissimilarly there was small wave of lamella interest in Germany in the early 2000’s, with the Dusseldorf firm,

Petzinka Pink adapted aspects of the form for a

showy hybrid timber-glass building; the offices and public face of the regional North Rhine Westphalia state Government in the country’s capital. Although the timber part of the office was a parabolic arch, Petzinka Pink paid tribute to Zollinger. A second practice,

Bottega + Ehrhardt Architekten, this time in Stuttgart, South Western Germany,

renovated an old Zollinger lamella structure to house offices in Ludwigsburg. The refit version shows just what can be done with the curving barrel arches of lamellas. Lamella as form has also returned to the US landscape. The well-known social and alternative architectural school,

Rural Studio, recently used a lamella form in 2007 for their

Hale County animal rescue centre in their home base state of Alabama. Long planned and started in 2005, the long barrel vaulted structure from a design by four of the Rural Studio’s students, who came up with a single sized, 2 by 8 joist which could fabricated repeatedly and seemingly endlessly for the main structure. With each small joist-piece precut to shape by students, the result is an elegant piece of woodcraftsmanship. Sitting on steel connectors, which ground the canopy to a concrete slab, the curving diamond lattice deck is sliced through by long horizontal slits for views across onto the surrounding neighbourhood. Among some of the more adventurous small UK practices, the lamella has also appeared. Ely’s

Mole Architects integrated a lamella shell into a competition to design a

rural visitor centre. If Mole had won there would likely be a lamella barn in the wilds of Norfolk.

and Bottega + Ehrhardt (Photo: Bottega + Ehrhardt)

Lamellas by Rural Studio (Photo: Rural Studio)

Despite this brief outbreak of lamella action across the western world, had the two Cullinan’s projects come through, the form would surely have gained a much higher profile and given its simplicity, economy and sustainability credentials would surely been taken up in a variety of other contexts. This, however, was not to be. By the time the Inverleith Botanical Gardens began a considerable time and elapsed from the still-borne Gaia Renewable Centre and Cambridge Botanics projects. Things had moved on, though also the hilly ground of the Edinburgh gardens militated against experimenting with lamella forms. Still, Costello, one half of the Cambridge Botanic project team, believes the experience researching and designing lamellas may yet be used again by the firm, the knowledge learnt having only been mothballed, to be picked up again as and when the appropriate project turns up. The same lack of further build contexts also applies to the W&D gridshell, which the practice actively promoted as an elegant solution for sports halls. There was, says Costello, a pretty interested client, though it never got off the ground. There were also various other, retrospectively fanciful, ideas. Virgin Air were apparently thinking of one as hangers for their expanding Heathrow operation. Other stories flourished but approaching a decade later, Cullinan’s produced neither further gridshells nor any on the ground lamellas; the Inverleith diagonal grid is the sole outcome of this intervening decade - floating above the ground on the second restaurant floor of Edinburgh’s botanic visitor centre. If this sounds small recompense for all the energy used for the various projects it is also graphically shows the frustrations that architects continually live with.

Mole's Model of their Great Fern Mill project which would have featured a lamella if it had been built

-------

Hunter House (Photo: Kew Botanic

Gardens)

There is a coda to this story of the Cullinan practices journey into botanic gardenland. In the mid 2000’s Cullinans became involved in a very different plant related building to Inverleith Botanic gardens. This is the, also recently opened,

Kew Gardens Herbarium extension. The Herbarium is part of the country’s national research facilities into plant life and flora and fauna, and Cullinans have provided a tasteful, restrained extension to an already large set of research buildings, situated at the edge of the gardens north eastern corner. The Herbarium originally began life when the country’s one time Dutch Ambassador, Joseph Banks (1743 – 1840) donated his Georgian home,

Hunter House, to the country. It became the first site for Kew Garden’s and it’s early research work. Comprising four wings, around an inner courtyard, Hunter House sits between a peaceful stretch of the Thames and Kew Green, just to the east of the Gardens main entrance. A long rectangular sixties block running parallel to the Thames. The Cullinans extension has been tucked into the north eastern corner, adjoining and extending out from two of the wings. Designed around a cylindrical foyer, which links to the corners of the two wings on its western side, and a North-South set of offices and plant processing centre to its immediate right. Looking through the tall iron railings, one can just about see the cylindrical entrance, the glass curtained, most overtly modernist gesture and public face to the new Herbarium extension. Walk fifty yards east, however, follow the small road leading round the edge of the grounds to the car park, and the timber clad eastern side of the office block emerges, almost hanging over the road, with balcony office extensions pushing out further from the bulk of the building.

Once the road’s corner is turned, with the Thames suddenly in front of you, the further interior face of the brick and wood clad office block comes into view. Partially masked by four old oak trees, when I visited these were casting long winter light shadows beguilingly onto the ochre red ground floor of the office resulting in a soft wavy undulation to the office extension. Generally there is a restrained presence to the office block, in amongst the well-to-do homes and houses that encircle Kew Green. Cullinan’s sense of restraint works well in such company, though one can also see that for a variety of reasons, not least a relativity tight site, and a need, apparently, to be very careful and design around four mature trees, as well as the unusual specialist facilities befitting the one-off nature of a species preservation facility and library, for a quite particular design for the building.

Kew Herbarium (photo: Tim Soar)

The vast majority of the herbarium’s actual specimens – 8 million and growing rapidly, are still in the main building. However with the collection doubling between every sixty and a hundred years – with approximately 300 species for each different plant and several examples of each – the need for the extra space to supplement the existing Herbarium facilities was becoming pressing. If the extension was planned to provide breathing space to the existing Herbarium, there was also a need for new facilities. This includes problems with pests, meaning part of the semi-separate research block is maintained consistently below 14 degree temperature, too low for pests to live. A small proportion of the plant specimens have been moved into the adjoining block, with ground floor and underground processing facilities which act as a kind of processing unit, freezing incoming seed and plant specimens. On the upper floors, those with the glass curtain windows at each end, further office and administration space is mixed with photography, storage rooms and other archiving facilities. Cullinans new block is the holding centre for what are called ‘type species’, the first specimens of a species, including those brought back to these shores by Charles Darwin. Within the foyer cylinder, designed around a concrete core, is the seed species library, and IT resources on the first floor and offices on the second floor.

Entering the foyer is also a reminder that Kew Herbarium is not a timber building, brick and concrete and steel predominate throughout. The linkage to Cullinans is in tracing their botanics trajectory, one which all those I spoke to at Cullinans confidently if diplomatically, believed would continue. These, perhaps, are hopeful words given the current economic circumstances the architectural world is facing. Meanwhile, back in Cambridge, early this summer saw the opening of the building which actually eventually superseded the botanic gardens visitor centre, the

Sainsbury Plant Sciences Centre laboratory by

Stanton Williams Architects. Alongside research into plant and a herbarium the Sainsbury building also includes a café, the part of the earlier interpretation and visitor centre, which has been held over from that earlier time. With Cambridge out of the picture it is left to the Inverleith building, with its myriad examples of recent trends in sustainable thinking to represent a whole period, in effect the last ten years of this specific line of Cullinan’s timber experiments which can be said to have begun with Hooke Park and flowered most fully with the Weald & Downland gridshell. It is a chapter in itself, encompassing this eclipse of the rural, exciting if abortive adventures with lamellas, and finally, an eventual showcase building in the heart of the Northern capital city. What began with such definite conscious rural flavours has, at least for the present time and in keeping with larger social trends, migrated to urban realms. It will be interesting to see if it stays there.