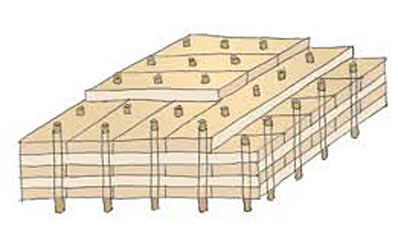

Brettstapel, a new name for an old technique.

Though less known across the sustainable building community, the lower tech, glue-less timber panel approach, has a long history. Now, as Dainis Dauksta writes, with new Brettstapel buildings being completed in Wales, British Columbia, Canada and continental Europe, the momentum for its resurgence is returning.

Massive timber construction methods that substitute fossil fuel energy-embodied materials such as concrete and steel with engineered wood products are now well developed. Glue-laminated timber (glulam), cross-laminated timber (CLT) and dowel-laminated timber (DLT or Brettstapel) are now accepted across the developed world as benign carbon-storing prefabricated elements within durable structures. Construction supply chains based on timber from managed forests effectively funnel carbon sequestrated from the atmosphere via trees straight into the fabric of the built environment. However this elegant net carbon equation only works when timber from sustainably managed forests is available.

Illustration, Brettstapel.org

Photo Sohm Hozbauteknik

Open Source/Wikipedia

The link between forest production and timber consumption by industrial societies was clearly laid out in 1713 by a Lower Saxony mining administrator called von Carlowitz who gave us the word Nachhaltigkeit or sustainability. His concept used the mensuration of sample trees in delineated forests to calculate their total annual timber volume growth or sustainable annual increment. In other words use industrial forests as natural bank accounts from which you only withdraw interest payments. Currently, productive planted forests pay their owners a much better annual increment than the cash in their actual bank accounts.

Globe Elevator silos

Given their history of attention to forest management and use of local timber in construction it isn’t surprising that central Europe is one of the most important centres of expertise in massive timber construction and the names Thomas Herzog, Gerhard Schickhofer, see feature on Schickhofer here, Wolfgang Winter and Julius Natterer are all closely associated with its development. Natterer is often attributed with introducing the concept of Brettstapel or dowel-laminated structural timber panels in the 1970s. This isn’t strictly true as nail-laminated fire-resisting heavy floor construction was widespread in northern American and southern Canadian cities before the 20th century. In the same region engineered-timber grain elevators or silos as we would call them used horizontal lamellae in nail-laminated walls. Some of these silos were huge and they dominated their surrounding landscapes.

Kaden/Klingbel – Photo Kaden/Klingbel

Natterer essentially gave an old method a new name. Brettstapel is a simple technique to manufacture structural wall panels and floors that can be readily applied by SMEs or at large economic scale. It can be carried out in a 20’ container on-site workshop equipped with only a cross-cut saw and clamps. High volume production methods can use clamping lines equipped with automatic nailing or boring and timber dowel inserting machines. CNC sawing, planing, routing and boring are all possible within factories to allow just-in-time delivery of finished panels to the construction site. Brettstapel factories in Germany, Austria and Switzerland have established efficient delivery methods that vary according to need and allow mid-rise structures to be built within days. Fast tractors with trailers can deliver to local construction sites whilst faster articulated trucks and trailers deliver further afield.

Dowellam was first mooted as an English term for Brettstapel by an Edinburgh Napier University working group that was established to research the application of the method using homegrown timber for low-carbon construction in the UK. The name Dowellam has been taken up by StructureCraft Builders, a firm based in British Columbia that is now developing a high-volume DLT production line. They use DLT’s unique properties to differentiate it from CLT. It is a 100% timber structural panel and DLT uses less timber than CLT to obtain similar structural performance. Their Abbotsford, BC, headquarters and DLT manufacturing centre at 50, 000 feet2, is according to StructureCraft the largest all wood building on the continent. Bespoke lamellae profiles can easily be machined in planer/moulders to deliver various refinements be they aesthetic, acoustic, structural or environmental. StructureCraft offer DLT made with many of the softwood species now growing in Britain; Sitka spruce, Douglas fir, western hemlock and western red cedar. They also claim that their DLT panels will be cheaper than CLT. More information is available here.

facility – Photo StrcutureCraft

Some UK commentators have suggested that low quality softwoods can be used for DLT. This is a misunderstanding and the word quality preferably needs to be applied to the finished product. There may be some scope for using lower value softwoods in lower quality DLT panels which are to be covered, for instance with plasterboard. However, fully machined and profiled DLT lamellae need higher-grade softwoods, not necessarily knot-free but certainly with strict specifications for knot sizes. Large knots can quickly damage profiling knives in planer/moulders leading to increased downtime and higher production costs. Beech is often used for the super-dry dowels that lock the softwood lamellae together but there are risks associated with this species, it can readily absorb moisture and beech dowels will transport water and fungal infections deep into DLT panels if they are wet for prolonged periods. A large social housing project using (imported) nailed DLT in Dublin had to be demolished after contractors allowed the panels to get wet during construction.

The Coed-y-Brenin visitor centre in north Wales by Architype was built during a very wet winter despite warnings by timber consultants; it was only the emergency ameliorative measures taken by the subcontractors which saved this project from failure. The common British practice of allowing buildings to become saturated during construction and then drying them out will not work with DLT. Plumbing needs to be impeccable in DLT structures; small leaks can spread very efficiently between lamellae and along dowels causing costly damage through fungal decay, mechanical expansion or both. More information about DLT here.

Photo Henrietta Williams for Architype

The British construction sector delivers innovative world-class architecture and civil engineering but is addicted to concrete and steel, materials which are far more forgiving of the wet climate we enjoy. Central European DLT manufacturers and the builders working with them have established working protocols for delivery of massive timber constructions and they have routinely built midrise glulam and DLT structures on time and within reasonable budgets. If the British are serious about lowering carbon emissions from construction, DLT could have a place in the wide spectrum of contemporary timber structures that can be made with homegrown wood. However any massive timber construction supply chain utilising softwoods from UK forests now faces the outcomes of poor policymaking. British timber growers and processors have been warning politicians for decades that we need to grow more conifer forests to contribute to sustainable construction. UK governments have ignored this message whilst subsidising the burning of homegrown timber through RHI payments. The weak pound currently makes imported softwoods more expensive and saw millers are suffering log shortages with concomitant rising prices of up to 40% on some species. If architects and developers are serious about implementing low carbon construction using home-grown timber they need to join the growing call for reforestation of British uplands.

With over 25 years of experience in the field of forestry and design of timber structures, Dainis Dauksta worked at Wood Knowledge Wales until recently, and has since started his own consulting form Wood Science Ltd

Dauksta has researched and written a number of reports on Brettstapel, including Welsh Softwoods in Construction

For further info on Brettstapel in Britain see www.brettstapel.org